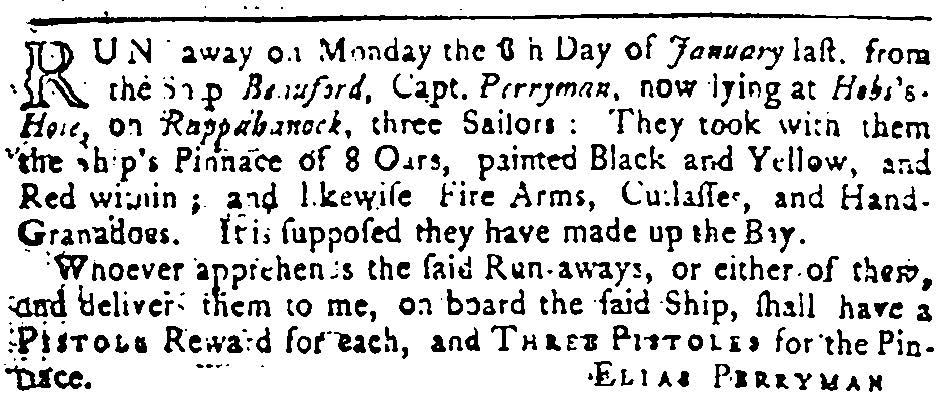

Richard Worgan has intrigued me because what little I have been able to discover about him has been curiously diverse. At various times his life brushed against some famous names and he became familiar to them, and yet the gaps in his chronology leave us with little explanation as to why the course of his life went in the directions it did. All I have been able to do is to provide what the accident of history has left behind and hope that it is an interesting narrative.

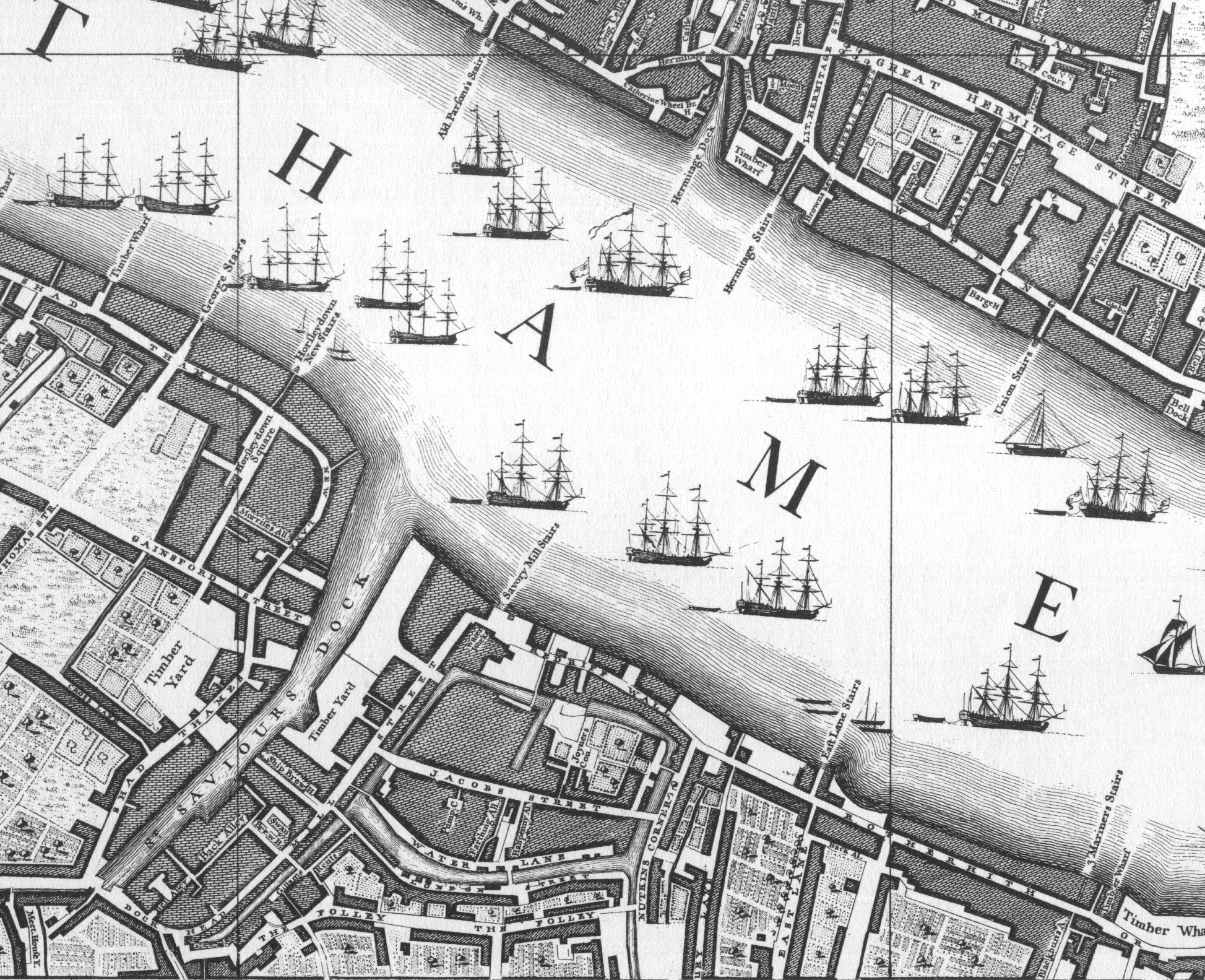

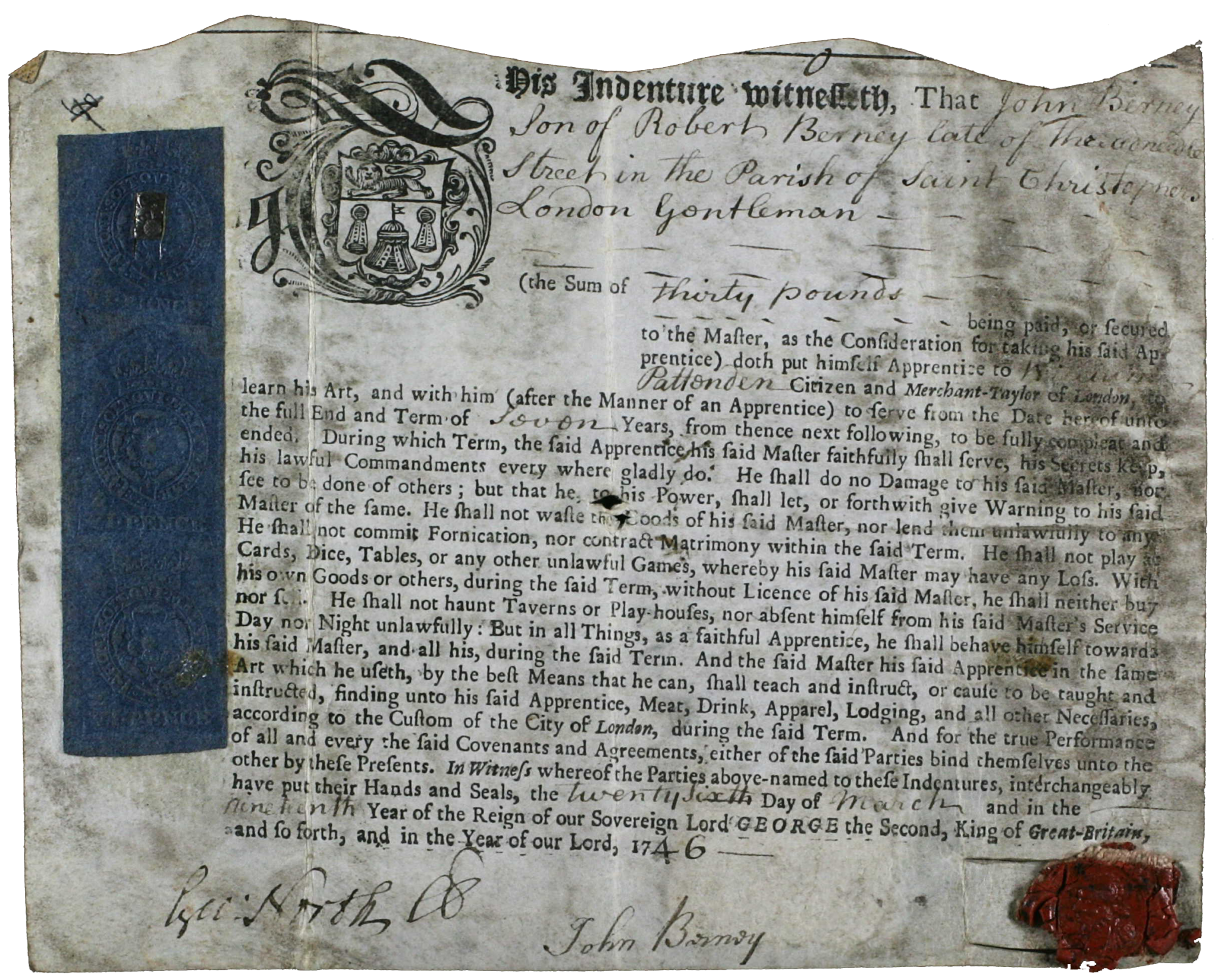

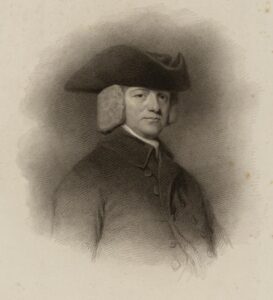

He was the fourth of the six sons of my ancestor Dr John Worgan and his first wife Sarah. He was born in 1759 and, like the rest of his siblings, at 7 Millman Street in Holborn and he was not quite 10 years old when his parents were divorced. As also with his brothers and sisters, the children of a celebrated organist and composer, he was taught music and he was to describe it as a recreation in later life, perhaps a slight understatement as will be seen.

His father remarried in 1770 and during his teenage years Richard grew up in the new household of his father and step-mother Eleanor at 40 Rathbone Place, Marylebone. He was only 16, though, when Eleanor died leaving his father still with young children to bring up, including Richard’s half-brother, Thomas, then only three years old. John Worgan married again two years later to Martha Cooke, a widow, but by then Richard was 19. What occupied him for the next five years is not known. He did not go to university, as his youngest brother Joseph would do, but whatever he did, he had evidently sufficient means in February 1784 to get married. The announcement was printed in the pages of The Gentleman’s Magazine:

MARRIAGES: Feb. 1. Mr Rich. Worgan, son of Dr W. to Mrs. Colebrook

No record in surviving church registers has been found of this union, so who Mrs Colebrook was, who she had been married to previously, or where they married remain a mystery. It will be seen, however, that the marriage was neither long nor fruitful, she perhaps succumbing to the fate of many women in those times, to die in childbirth; but that is speculation.

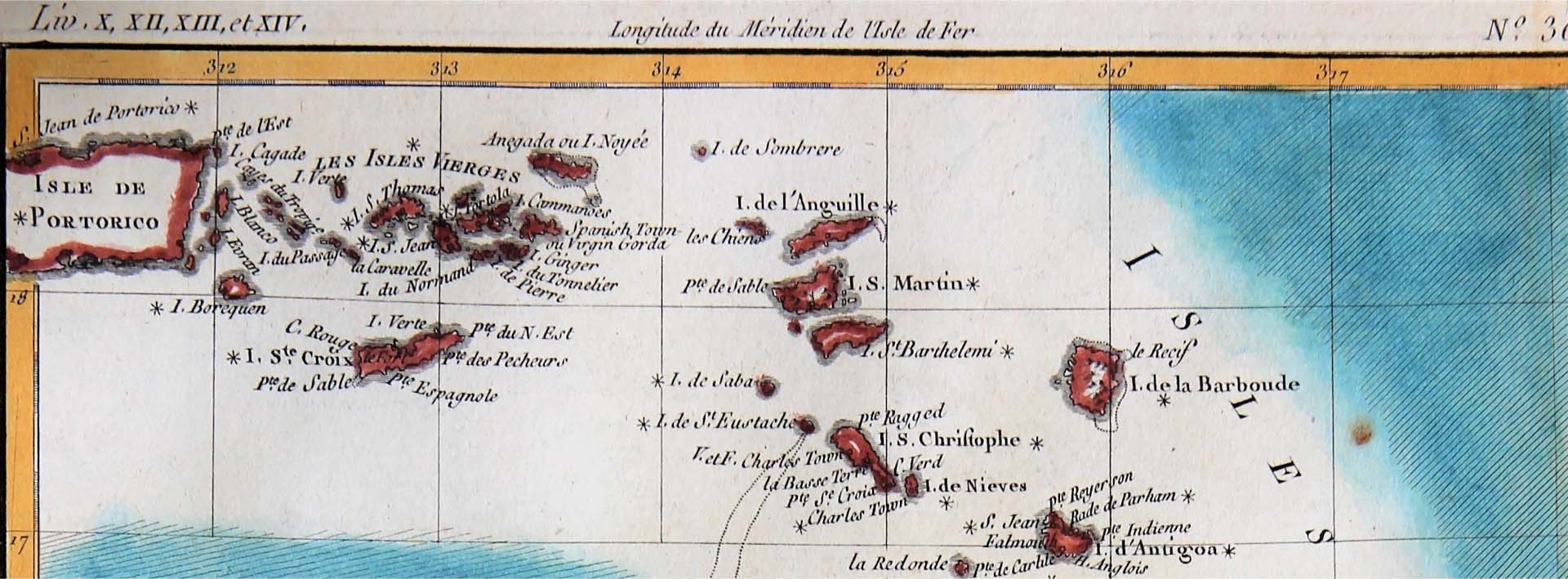

We hear of Richard again in 1789 when insurance records show that he had a property at 7 George Street, a recent development north of Portman Square in Marylebone. In that year he was the recipient of a lengthy letter and account from his older brother George, a naval officer, who had been one of the surgeons on HMS Sirius, the flagship of the First Fleet carrying convicts to Australia. Arriving in January 1788, George had sent the letter to Richard on one of the ships returning to England in July of that year, a journey of at least six months. Notable as a historical document, it was a first-hand account of the establishment of the settlement at Port Jackson and of George Worgan’s experiences during the six months since his arrival. Like Richard, George was a musician and took a piano with him on the Sirius, leaving it behind in Australia when he returned home. He arrived back in England in 1792.

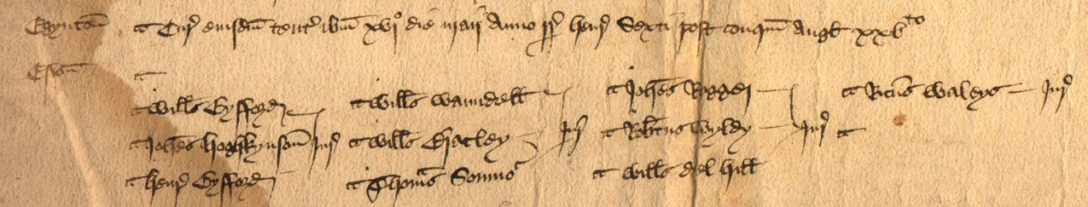

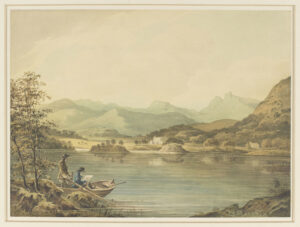

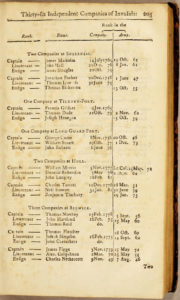

Richard Worgan was in Yorkshire in 1794. In June of that year four of his settings of parts of psalms were published in Improved Psalmody, a collection of such pieces by a number of composers edited by William Tattersall. Among the other composers were Richard’s 18-year-old half-brother Thomas Danvers Worgan and his brother-in-law William Parsons, the husband of his sister Charlotte. Parsons had been appointed Master of the Musicians in Ordinary to the king, George III, in 1786. Richard and Thomas Worgan were among the subscribers to the publication, both described as of Yorkshire; also a subscriber was a Miss Worgan of Somerset Street in London, Richard’s younger sister Maria, who lived with the Parsons.

Richard’s and Thomas’s presence in Yorkshire was further noted two months later when the following marriage notices appeared in the Chester Chronicle:

8 Aug 1794: [Monday] at West Wittson, Yorkshire, Mr R. Worgan, musician, to Mrs. Lawson, relict of the late Rev. James Lawson. – Same day, Mr Thomas Worgan, to Miss Lousdale, sister to the above lady

James Lawson, clerk (in Holy Orders, that is), had married Jane, daughter of George Lownsdell, a cabinet maker, in Sunderland in 1772. They had four children, all born in West Witton, where James was the vicar: Elisabeth in 1774; James in 1776; Mary Ann in 1780; and George in 1784. So when the Reverend James died in May 1794 the older three were in their teens and George was 10.

To have married Jane so soon after she had been widowed, Richard Worgan must have been well acquainted with the Lawsons, which begs the questions: why was he in Yorkshire and where had he been living? Unfortunately the marriage register for West Witton, where that information might have been found, is not available. In his will, made in March that year, James Lawson left his house to Jane, so she and Richard probably stayed in West Witton, where in January 1799 Jane’s 18-year-old daughter Mary Ann died and was buried. Interestingly, when Jane obtained probate for James’s will in January 1795 it was as Jane Lawson, not Worgan. Was that because it was as Jane Lawson that she had been named in the will, or was there some other reason?

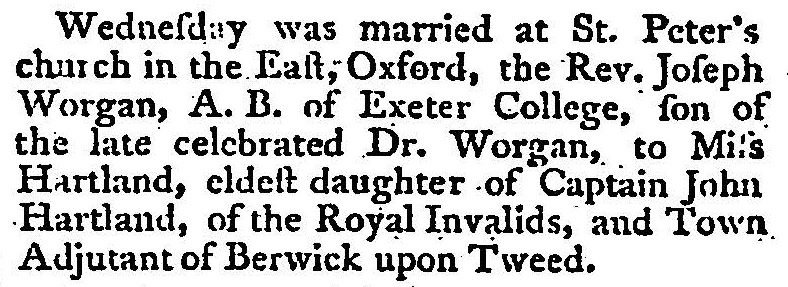

The absence of the marriage register also prevents us from knowing the name of Jane’s sister, who married Thomas Danvers Worgan on the same day. Thomas was 21 and given that Jane Lownsdell must have been at least 18 when she married James Lawson in 1772, it can be reasonably assumed that her sister was quite a bit older than Thomas. It is likely that he and his new wife lived in London, for in 1796 Thomas obtained the position of Sergeant at Arms at court, probably achieved through the influence of his half-sister’s husband Sir William Parsons, the Master of the King’s Band, who had been knighted the previous year.

It is eight years before we hear of Richard Worgan again. In November 1802 he was in Highgate, then a village to the north of London, because of the death of his younger brother James, a musician, aged only 40. A bachelor, James had appointed Richard his sole legatee and executor, and within a week of James’s burial on the 19th Richard had obtained probate enabling him to sort out his brother’s affairs, which will have included his instrumental and choral compositions.

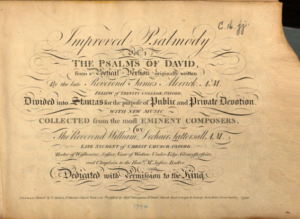

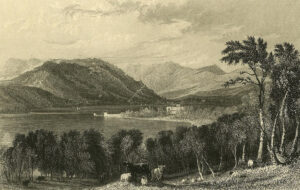

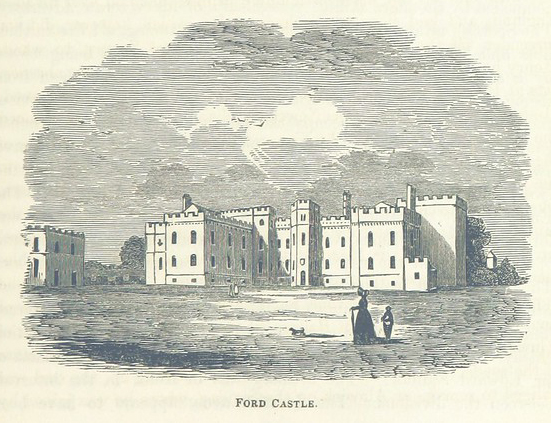

In 1804 Storrs Hall, a mansion near Bowness on the banks of Lake Windermere, had been purchased by David Pike Watts, a former London wine merchant, who had inherited a fortune from his late business partner and who was devoting his life to charitable acts. To assist him in this he employed an almoner whose job, presumably, would be to organise the distribution of this charity. Richard Worgan secured that position and was given accommodation in a cottage on the Storrs Hall estate. From the lack of any reference to her, it is uncertain whether Jane Worgan accompanied Richard.

Also in 1804, the poet Robert Southey, later to be Poet Laureate, took over his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s former home at Greta Hall, near Keswick. The two of them, together with William Wordsworth, who had returned to the Lake District five years earlier, formed a literary relationship, which came to be known as the Lake Poets, attracting others to the area over the ensuing decades. Richard Worgan was on the periphery of these figures and his musical skills brought him into their orbit. In November 1804 Southey wrote to his old school friend Charles Wynn:

I have met a very odd homo by name Worgan whom if you have not seen you will for he is going to Acton this Xmas. he does wonders upon the piano-forte. oddly enough he played & sung the Old Mans Comforts [Southey’s poem of 1799] in a large company, & after praising the music they fell to praising the poetry, which nobody knew to be mine. He himself fancied it was Bowless – so I set him right.

Who or what Richard was visiting in Acton is not known. A week earlier, Southey had written to his brother Henry:

Mr. Worgan & I pun against one another with great glory. Alas what will not the world lose for want of a Boswell!

Also arriving in the lakes in 1804 were John and Jessy Harden, who rented Brathay Hall, near Ambleside. John was a water-colourist of Irish descent, while his wife was a diarist, born in Edinburgh. They joined in with the literary and artistic circle and Jessy’s journals reveal their friendship with Richard Worgan, making frequent visits to his cottage and gathering there with friends or on Lake Windermere. Richard’s musical talents provided an extra dimension to their social gatherings, and he was able to make use of some of the other buildings on the estate to entertain them, such as the Temple of the Heroes, an elaborate summer house built by the previous owner of Storrs Hall. Richard even acquired a portable barrel organ which could be taken on boat cruises on the lake.

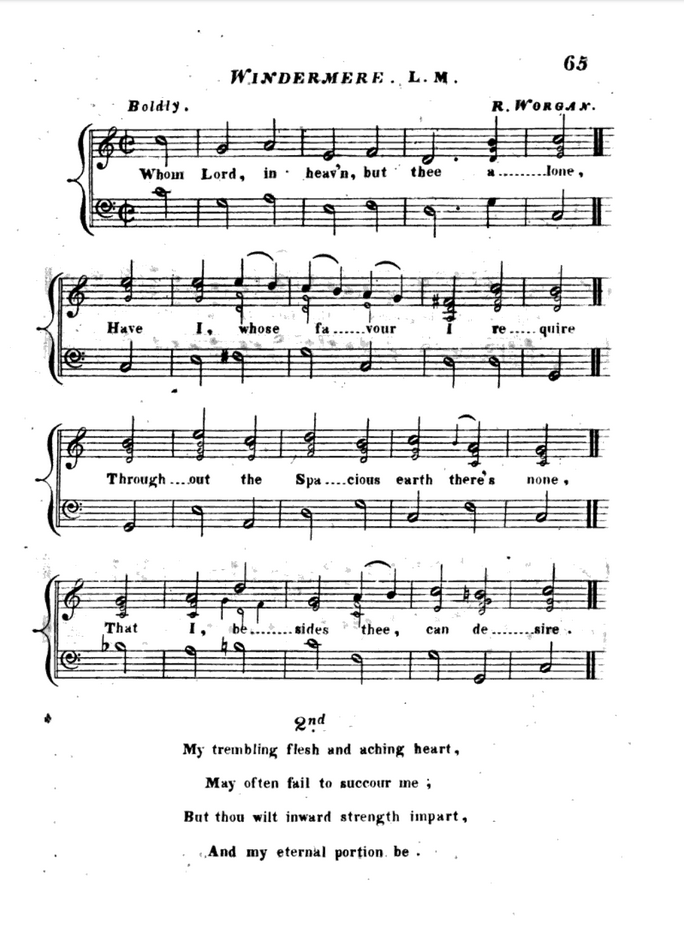

David Pike Watts was the brother of Ann Constable, mother of the painter John Constable, and it was Watts who encouraged John to visit the Lake District in the Autumn of 1806, paying his expenses to enable him to pursue his artistic calling. Finding Lakeland uncongenial, however, Watts sold Storrs Hall at that time, so Richard Worgan must have come to some arrangement with the new owner John Bolton to continue to live in the cottage, for when John Constable and his friend George Gardner arrived at Storrs on 1st September they stayed for a week, not with Constable’s uncle, who had already sold up, but with Richard, before moving on to Brathay Hall and the Hardens. Drawings by John Harden show Richard at Brathay where he entertained the company on the piano. He composed a piano piece entitled ‘Windermere’ to which words were later set when it was included in Gems of Sacred Melody, a collection compiled by Richard’s nephew, George, son of his younger brother Joseph, that was published in 1841.

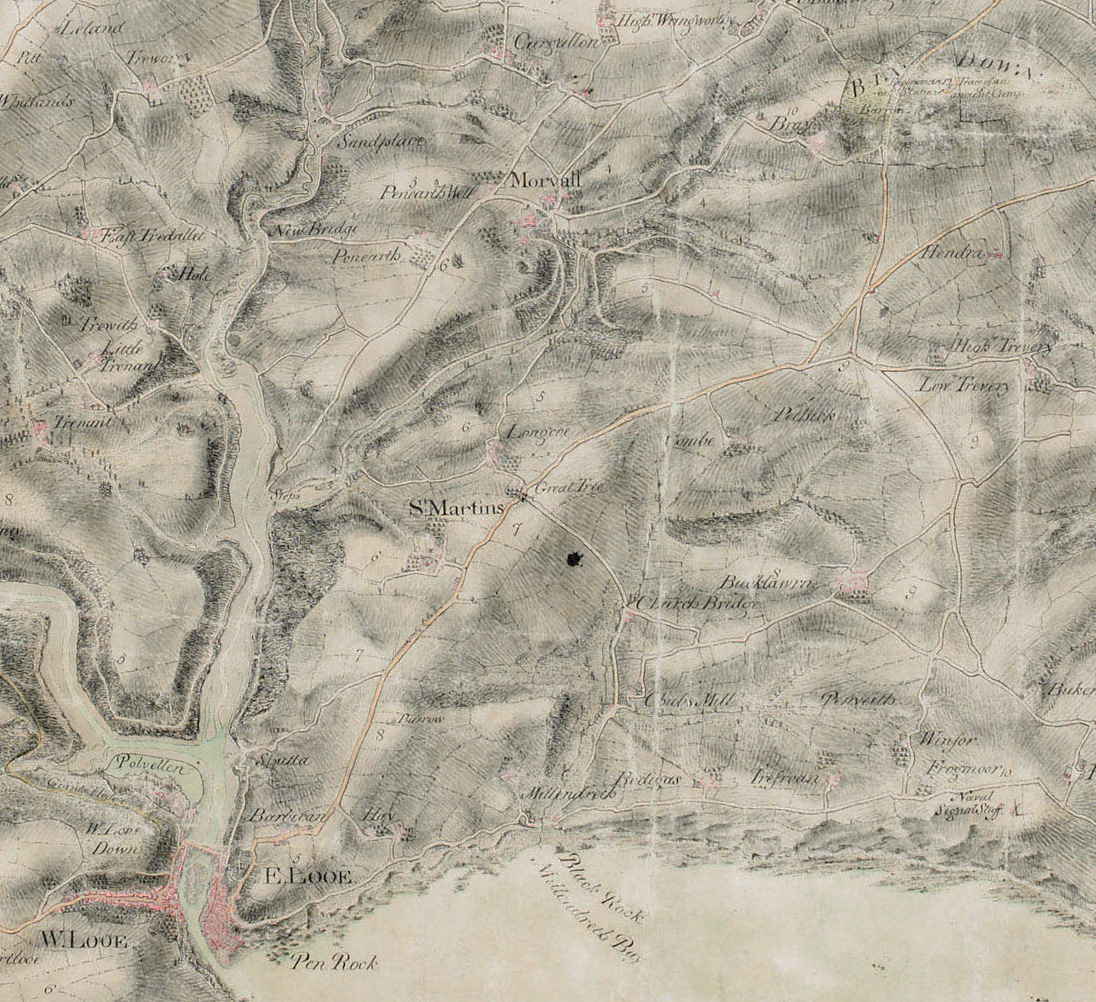

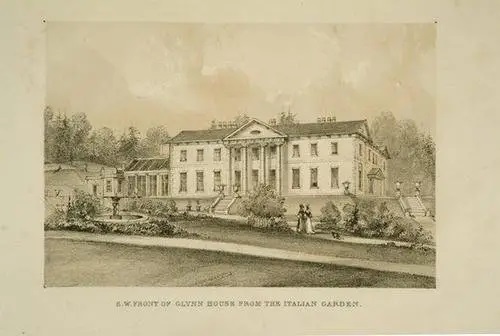

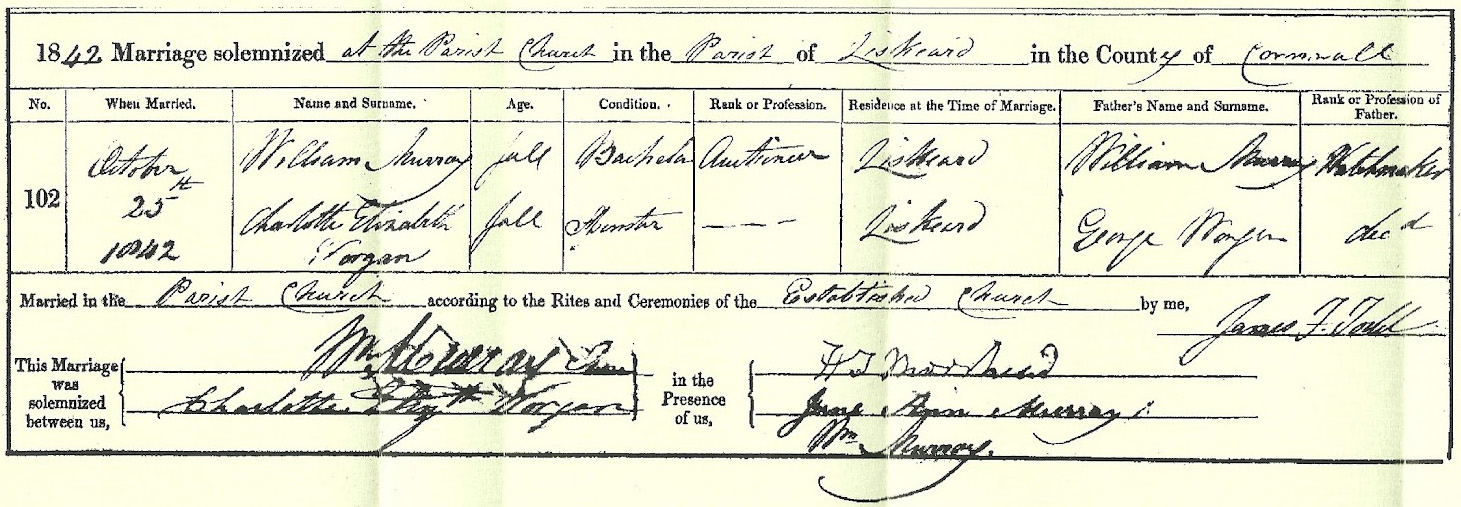

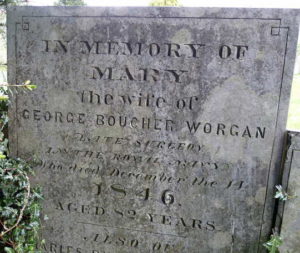

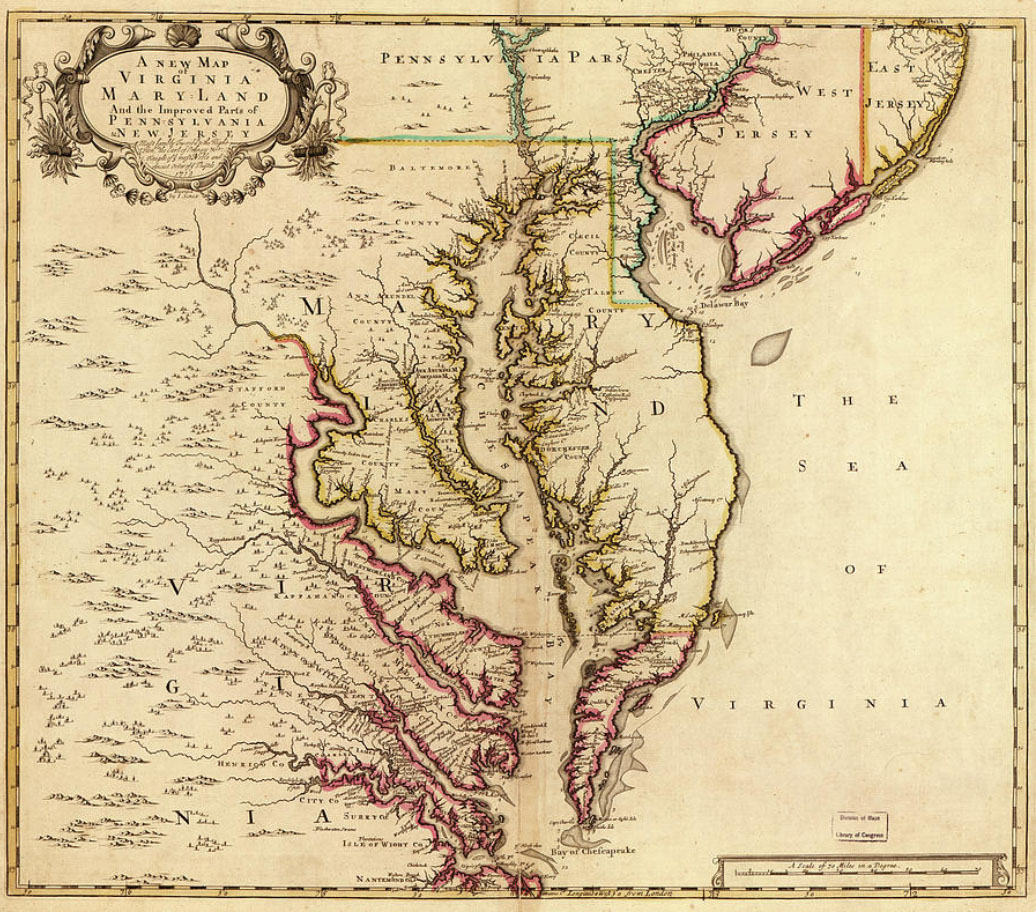

From 1807 Richard began to be engaged in correspondence, on behalf of his brother George, with Arthur Young, of the Board of Agriculture, in support of finding George suitable employment. After returning to England from Australia George remained in the navy for five more years in a shore posting in Plymouth, during which time he married. Following his retirement from the navy he took up farming at Morval, north of Looe in Cornwall. In 1804 he took on another farm, in Cardinham, but that was not a success and he was forced to abandon farming altogether two years later. For a couple of years George struggled to find employment. However, notwithstanding his failure as a farmer, strenuous lobbying by their sister Dame Charlotte Parsons, who used her social connections to full effect, persuaded the Board to offer George £100 to revise an earlier review of the county’s agriculture. When he submitted it a year later it was not received with approbation and had to be further revised by some of his former collaborators. Nevertheless the General View of the Agriculture of the County of Cornwall by GB Worgan was published in 1811 and was reprinted in 1815. Richard was still living in the Lake District, giving his address as Laurel Cottage, on Lake Windermere, when in 1807, in gratitude, he invited Young to visit and wrote the following:

Perhaps you will think me but a stupid clod, when I tell you that altho’ I love a country life, yet I do not fish, hunt or shoot though only a middle aged man, but for these sixteen years [i.e. since 1791] have devoted my hours to the study of divinity, Physic & farming and by way of recreation music … With the first I am endeavouring to save my own & the souls of others – with the second I am enabled to attend all the poor sick people around who amidst our mountains are dreadfully off for medical advice … Farming I have given up least like my brother I should burn my fingers so that now altho’ my income is very small, yet I live independent not liking to follow any profession for profit.

Did 1791 signify a change in his situation, his first wife dying perhaps? His devotion to ‘divinity, Physic & farming’ suggests strands in his life for which we have no other evidence save for the fact that whatever farming he had carried out hitherto he had ceased by then. Had he considered offering himself for the priesthood or entering the medical profession, or were these merely the interests of a dilettante as his final comment about not wanting to follow any profession seems to imply? In a second letter, Richard went on to explain his Christian beliefs, recognising a kindred spirit in Young and mentioning their mutual acquaintance, Dr Richard Watson, Bishop of Llandaff, who had a house at Rydal, north of Ambleside. In July 1808 Richard visited Arthur Young at his home, Bradfield Hall in Suffolk, a stay intended to be of a few days that evidently extended to five months.

Still living in the Lake District in 1810, Richard made a setting of some sonnets ‘Dedicated to Mrs B Gaskell of Thornes House by her friend Richard Worgan of Windermere’. The former Mary Brandreth, she had married Benjamin Gaskell MP in 1807. Thornes House being in Wakefield, Richard’s links with Yorkshire had been retained.

****

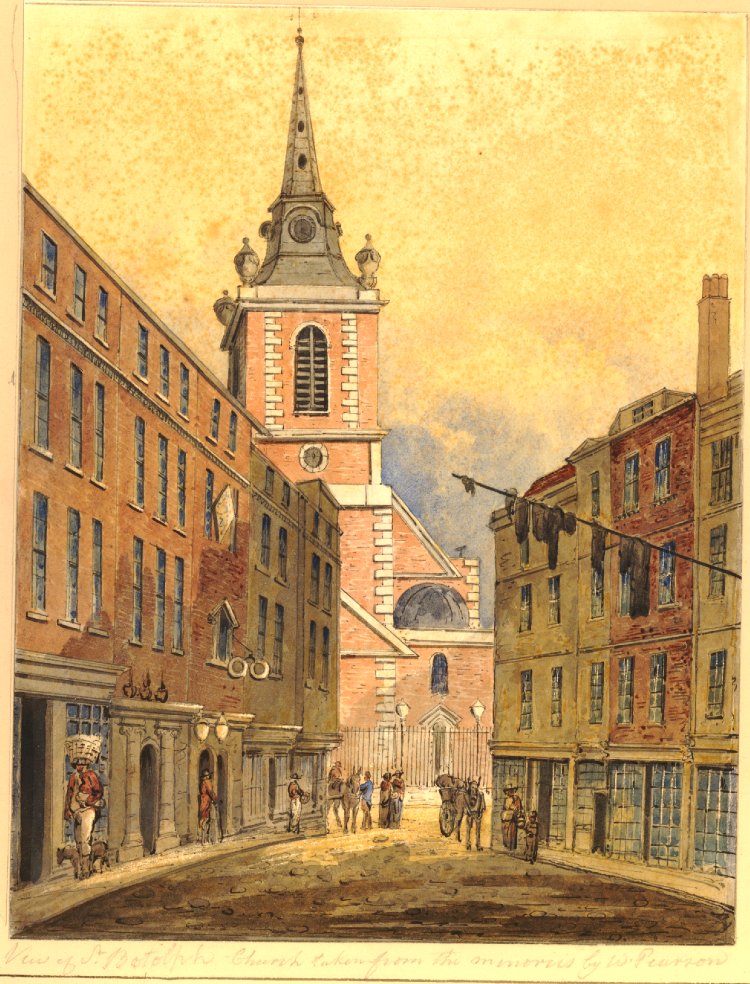

In November 1824 Richard Worgan was mentioned in a letter written by the younger Charles Wesley, who had been a pupil of Richard’s father and had played the organ at his funeral in 1790. The letter was to John Langshaw, whose father had also known Dr Worgan, being his sometime assistant organist, and who had subsequently been a maker of barrel organs. It might have been one of Langshaw’s that Richard had used when at Windermere. In the letter Wesley mentions in passing that Richard was then organist at Chester, though where in that city was not stated.

****

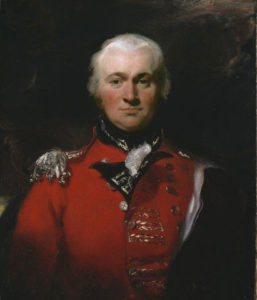

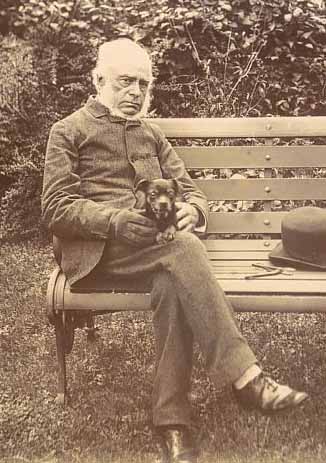

After that, nothing more is known of Richard until his sudden death, aged 80, during a visit to Holloway in north London, in April 1840. He had been living at Prestbury, near Cheltenham. His will makes no mention of his wife or her children, perhaps by then a distant memory. Family bequests, instead, were to his nephews and nieces, the four surviving children of his brother Joseph. Included was a portrait of his father by Russell, presumably the fashionable and prolific pastelist John Russell (1745-1806) whose portrait of Arthur Young is shown above. Also Richard bequeathed a portrait of himself ‘by the younger Wilkin’, possibly Henry Wilkin. The whereabouts of neither of them is known, alas.