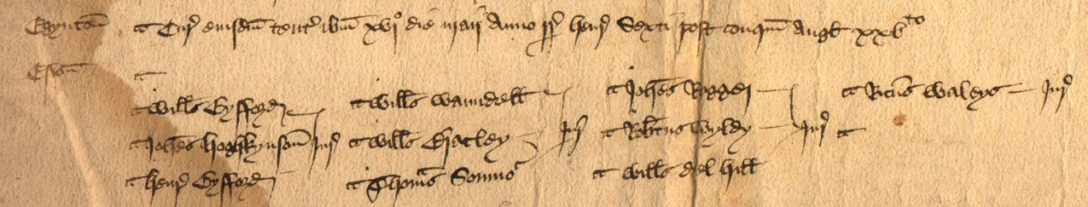

The earliest of my Spencer ancestors that I have been able to identify is Samuel who married Ann Byrt in Shepton Mallet, Somerset, in 1721. The Byrts go back rather further to Ann’s grandfather Thomas in 1666, but I have been unable to trace the Spencers any further. Samuel and Ann had four children, the first of whom died at less than two months old. I am descended from the next oldest who was named after his father. He married twice, firstly to Deborah Pender in 1758, but she died childless only four years later, and again in 1764 to Mary Smith who came from Wells. They had two sons, John, from whom I am descended, and William.

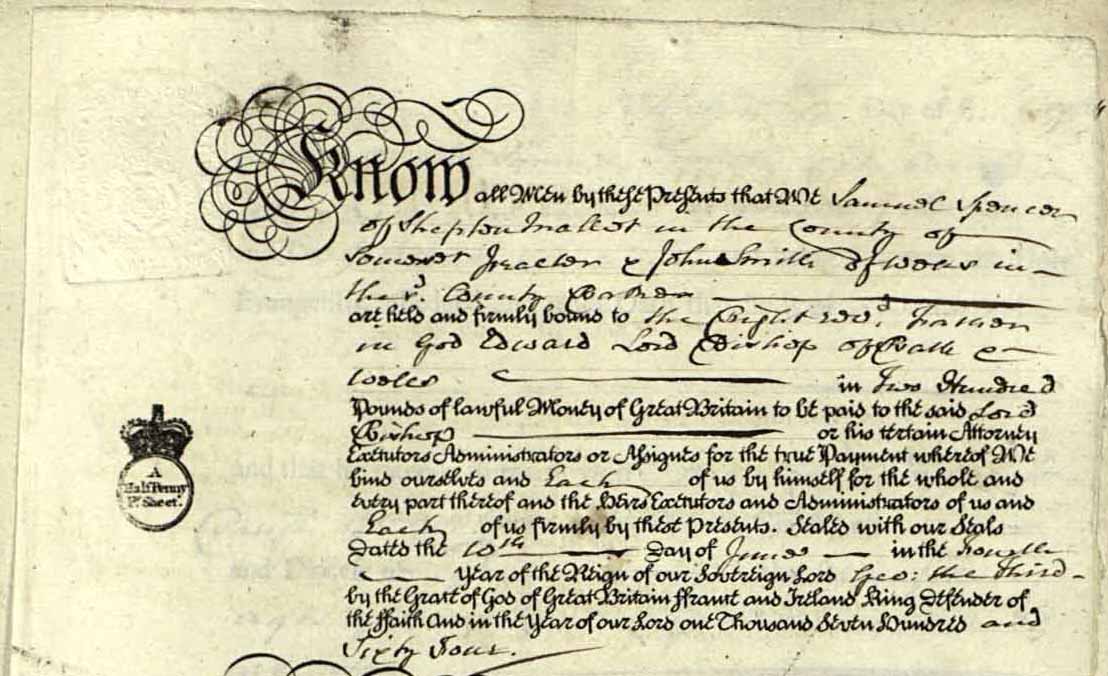

Samuel died in 1771. Mary had two young children to bring up but outlived Samuel by more than 40 years. In the fullness of time, John, the elder son, became an important local figure. He married Elizabeth Plummer in 1792. It is said that he ran the Blue Boar Inn in Shepton Mallet, and in 1804 was local Overseer of the Poor. By 1800 he had joined a partnership at the Oakhill Brewery, three miles to the north of the town. The brewery had been established in the 1760s and John Spencer’s was to be the start of a family involvement that would last more than a century. Somewhat at odds, one might think, with his role as a brewer, John was also a deacon of the Paul Street Independent Chapel, but in those days beer was an acceptable domestic drink because its low alcohol content killed the bacteria found in water. After Elizabeth Spencer died, in 1824 John married again. His second wife was Caroline Llewellyn, of Chelsea, a widow about 20 years younger than he.

Of John and Elizabeth’s seven children, the eldest son, William, became an army surgeon serving in the Sikh wars in India in the 1840s. The other two sons, John and Henry, followed their father into the brewing business. Henry, my great-great-grandfather, was born in Shepton Mallet in 1806 and in 1832 married Elizabeth Coles at St Cuthbert’s church in Wells, where his grandparents had also married. Elizabeth came from a family of papermakers who ran the Glencot Mill and later the Henley Mill near Wookey. They had three children, William Henry, Charles James, and Mary who was known in the family as Polly. William went to Cambridge University, where he graduated MA in 1867 and then went on to take a degree in medicine. He was a physician at Bristol Royal Infirmary for 16 years from 1872 during which time he graduated MD. With his wife Maryanne he had four children, among whom was Alexander who followed his father into the medical profession, serving as civilian medical officer at Middelburg ‘concentration’ camp during the South African War. However, it seems that after William moved to a position at the Hastings, St Leonards and East Sussex Hospital, he fathered two girls, Kathleen and Winifred, by a former nurse whom he had probably known when he was working in Bristol; they apparently turned up after his funeral in 1910.

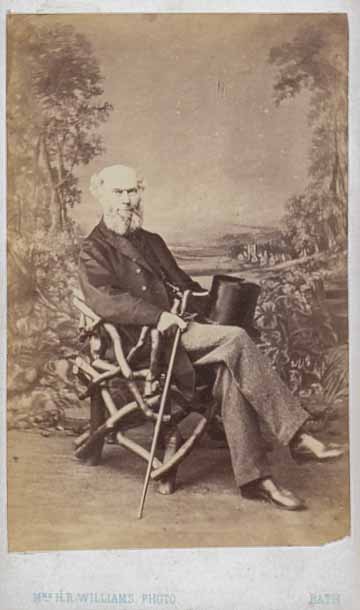

My great-grandfather Charles chose to pursue a career in mechanical engineering, and he may have been encouraged in this by his first cousin, John Frederick Spencer, son of his uncle William, for in the 1861 census we find him living, aged 22, in Elswick, a suburb of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with his occupation given as ‘engineer’s apprentice’. His cousin, who was 13 years older and a Consulting Engineer, was living a few miles away in Tynemouth. At Elswick, which was an otherwise undeveloped area, were the works of Sir William Armstrong, the arms manufacturer, and it is probable that Charles was apprenticed there. Six years later and he was in London. In the meantime he had probably worked for Frederick Ware, who had the Steam Boiler Works at Stratford, for in 1867 they were jointly granted a patent for ‘improvements in steam boilers’. However, the address given for Charles on the patent was 4 Queen Street Place, which is just north of Southwark Bridge, and which were the offices of Bessemer and Longsdon, iron and steel makers, so presumably Charles had left Stratford to work for the man who revolutionised steel making, Henry Bessemer.

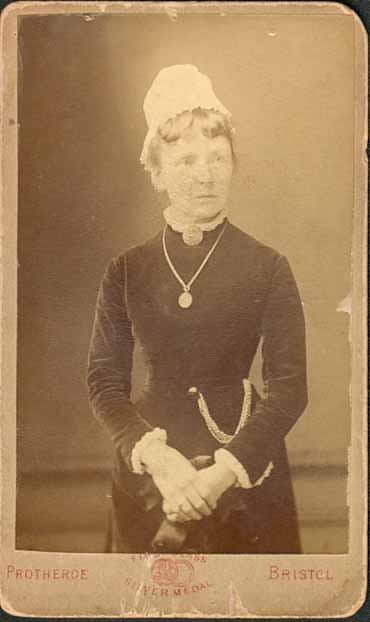

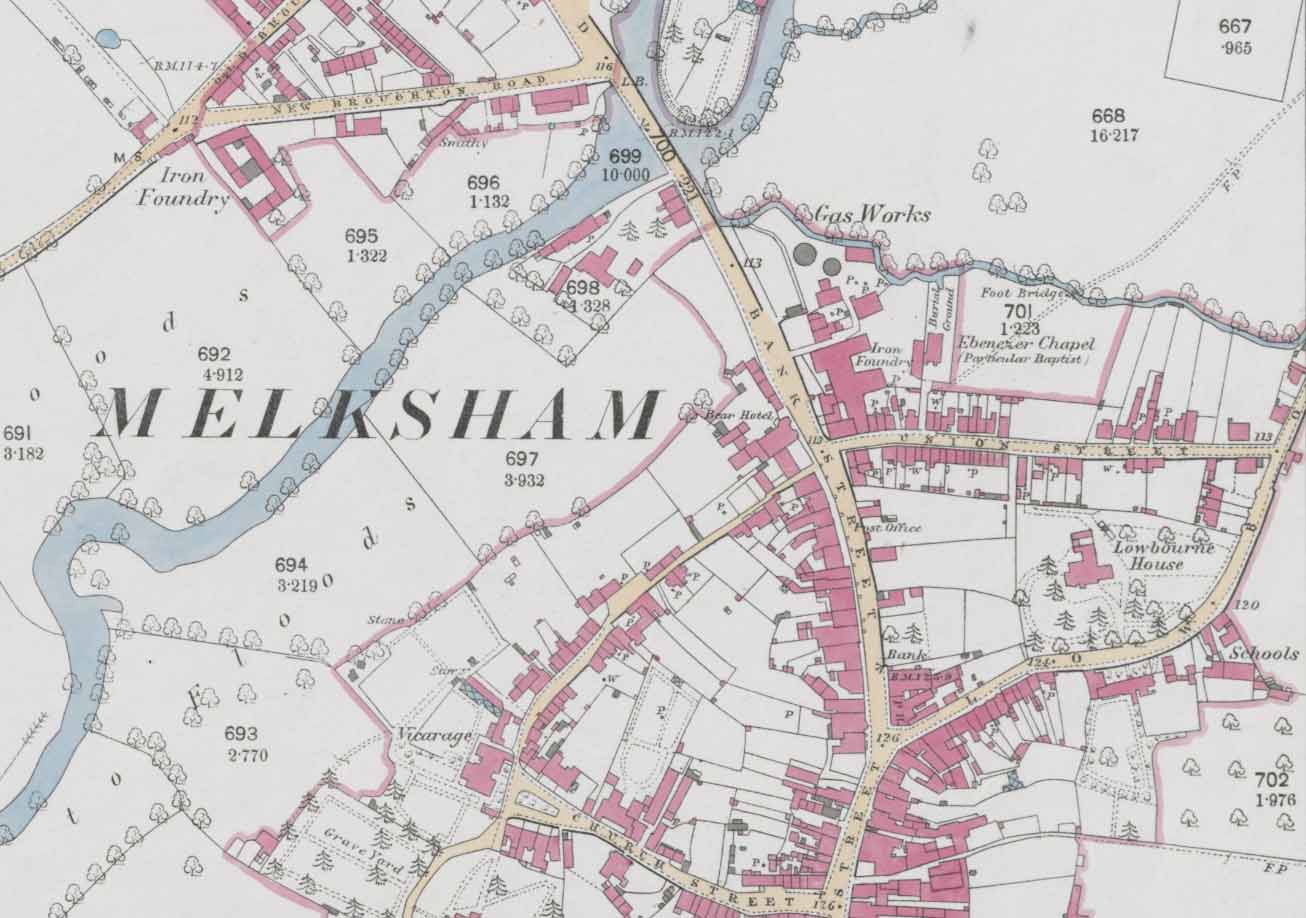

Four years later, in 1871, and after a long engagement, Charles married Emily Simpson, whose father had been a Lancashire cotton manufacturer (see My Gillett forebears). They were to have twos sons and two daughters: Wilmot, Kathleen, Maurice and Dora. Their first, my grandfather Henry Wilmot Spencer, was born in 1872 in Preston, where Charles was working in the cotton spinning business, a job found for him by his father-in-law. Kathleen came along two years later in Chester, which suggests that Charles had abandoned working in the Lancashire cotton mills, which apparently he disliked anyway, and returned to engineering work. Maurice, was born in Melksham, Wiltshire in 1878, the year in which Charles joined in partnership with John Gillett (no relation, it seems) as hydraulic engineers and millwrights at an iron foundry there that Gillett had established a few years previously. Two years later Dora was born at their new home at Westbury on Trym, more than 30 miles from Melksham; a long commute. My mother’s cousin Ursula wrote that apparently Emily did not like to stay in the same place for more than a couple of years, so by 1891 they had moved to Lyncombe, a suburb of Bath, somewhat nearer to Charles’s work.

John Gillett retired in 1884 and the firm continued as Spencer & Co until Charles also retired in 1894, after which it was renamed Spencer’s (Melksham) Ltd, moving to larger premises in about 1900 and continuing in business until the 1980s (though without any family involvement). Financial help in expanding the business while Charles was still in charge was obtained from William Isaac Palmer, one of the brothers who owned Huntley & Palmer, the biscuit manufacturers of Reading, who was a cousin of Emily Spencer.

Wilmot Spencer also became a mechanical engineer and for a few years in the early 1890s worked at Spencer & Co. in Melksham, as well as with other firms as far afield as Blackburn in Lancashire and Cowes in the Isle of Wight. By 1904, when he married Daisy Graham, he was working for the Crosby Steam Gage [sic] and Valve Co. in Victoria Street, London. They were an American firm based in Boston, Massachusetts, which made parts for boilers. Being an engineer he was in a reserved occupation during the First World War and, like other workers involved in the production of munitions and other supplies for the war effort, he was given a badge to protect him from accusations of cowardice. In the 1920s he joined another American company, Liptak Furnace Arches Ltd, also in Victoria Street and in the same line of business, retiring as managing director in 1937. He and Daisy had three children: Dorothy, who emigrated to Canada in 1936; Basil, who joined his father at Liptak; and Mary, known as Mollie, who was my mother.

In retirement Wilmot and Daisy moved to Bexhill, where Mollie met my father after the war, and following Daisy’s early death, Wilmot eventually came to live with my parents, my sister and me for a couple of years before he died in 1956.