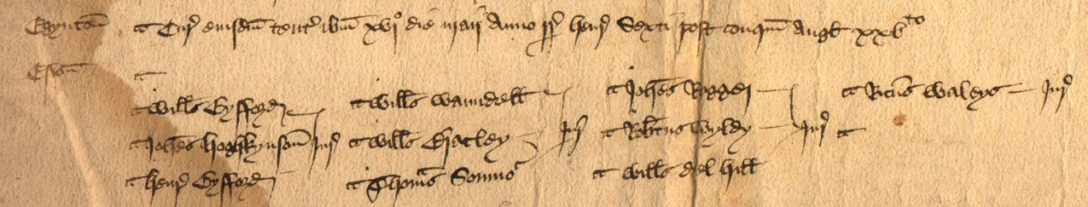

This is probably the most interesting family from which I am descended. I can trace the Worgan family (pronounced Wergan) back to the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire in the 17th century where several branches of the family farmed in Newland parish. The earliest of my Worgan ancestors of which I am certain was my great7-grandfather, John (I), who apprenticed his son of the same name to John Skinn of the Worshipful Company of Pewterers in London in 1679. Several other young Worgans from the families in the Forest were sent to London as apprentices at around the same time, drawing upon a network of family and other local connections. The Skinn family also came from Dean. John (II) gained his Freedom in about 1686 and married Elizabeth Hubbard in May of the next year. The oldest of their five children, two of whom died in infancy, was my ancestor, another John (III) who was baptised at St Botolph’s church, Bishopsgate, London, on 25 March 1688.

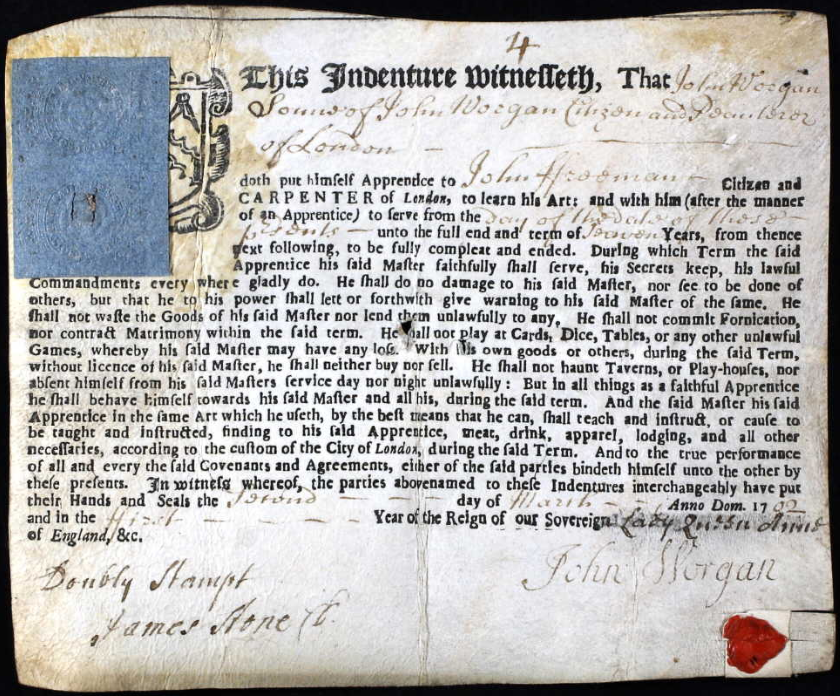

When he was 14 years old, John (III) was apprenticed to John Freeman of the Carpenters’ Company. Having been born after his father had served his apprenticeship, the younger John would have been entitled to be admitted to one of the livery companies ‘by patrimony’, but clearly his father felt it was important that the boy should learn a trade so he committed him to seven years of ‘servitude’ instead. On completion of his training in 1710 John went on to become a surveyor, writing a couple of books on the subject and getting into a rather public debate on one of the claims he made with a certain Charles Leadbetter, author of The Royal Gauger, or Gauging made Perfectly Easy. You can read Leadbetter’s comments HERE.

John Worgan married Mary Lambert at Grey’s Inn chapel in 1711, and they went on to have nine children, some of whose lives reflected the growing freedoms enjoyed by London’s citizens. James, their eldest son, became a musician, being a composer of songs and an organist. From 1737 he played the organ at the Vauxhall Gardens pleasure grounds, and from the following year held the post of church organist at St Botolph’s, Aldgate, and at St Dunstan’s in the East. He died, aged only 40, in 1753. His post at St Dunstan’s was competed for, and won, by his sister Mary, a first for a woman in the City, although she resigned a week after her election upon her marriage to Liell Gregg, a teaman; married women were not being permitted to be gainfully employed. Her younger sister, Hannah, married John Clarkson, a silkman, who had been apprenticed in the Ironmongers’ Company to his father. The youngest in the family, Charles, also had musical training which he was to employ in Jamaica whence he emigrated and become a sugar planter, playing the organ at Port Royal, formerly the island’s capital.

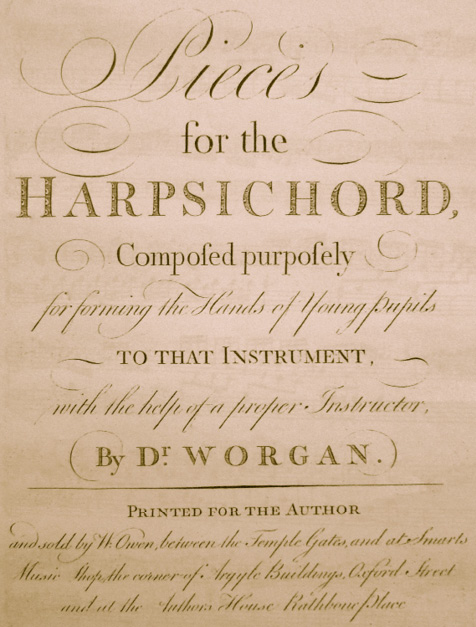

My great4-grandfather, John (IV), born in 1724, became an even more celebrated organist, playing and composing songs for Vauxhall Gardens in succession to his brother James. Eleven years younger, he was a pupil of James, and later of Thomas Roseingrave and Francisco Geminiani. His first post was at St Katherine Creechurch, when he was only 19. He gained the degree of Bachelor of Music at Cambridge, and from then on was appointed at several city churches in succession and sometimes concurrently. In 1753 he married Sarah Mackelcan, who had been a pupil of his brother James and whose father was a sugar refiner with premises in Cheapside. They set up home at 7, Millman Street in Holborn, where their nine children were born. In addition to his commitments at Vauxhall and at churches, John Worgan had pupils, he composed organ and harpsichord music as well as a couple of oratorios. Given the time it took to travel between engagements in those days his time at home must have been quite limited. To fulfil his organ-playing duties he engaged deputies, and this led to a serious scandal.

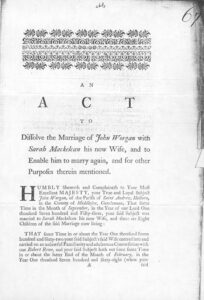

In 1767 Mary Gregg, John Worgan’s sister, discovered that Sarah, his wife, had been having a liaison with at least one of his deputies and a pupil, and on being informed of the affair John decided to commence proceedings for divorce. In those days divorce was a rare occurrence as it involved a two-stage process, firstly in a church court to annul the marriage, and secondly by private Act of Parliament to allow John Worgan to remarry. The case was heard in the Consistory Court of the Diocese of London through the summer and autumn of 1768. The case was then repeated before Parliament with Royal Assent to the Act being given in March 1769. A detailed account of the marriage of John and Sarah Worgan can be READ HERE

One of John Worgan’s sons, George, was a naval surgeon on HMS Sirius, the flagship of the First Fleet to Australia in 1788. Also an accomplished musician, he took a piano with him, and when he departed a few months later he left the piano behind, the first in the Antipodes. George later retired to farm in Cornwall. He wrote an account of his experiences in Australia for his brother Richard, which has been subsequently published as ‘Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon’. Two of George’s sons later emigrated to Australia. Richard and another of George’s brothers, John (V), were also musicians, and in 1778 Charlotte, one of their three sisters, married William Parsons who later became Master of the Musicians in Ordinary to the King (Master of the King’s Music as it would be now) in 1786. Also a stipendiary magistrate, he was knighted, ‘more on the score of his merits than on the merits of his scores’ it was said, in 1795.

John Worgan (IV) remarried after his divorce from Sarah. With Eleanor, née Baston, he had two sons although only one, Thomas Danvers Worgan, survived. He went on to become a musicologist. Eleanor, however died after only seven years of their marriage and with at least one young son, John Worgan married for a third time to Martha Cooke, a widow. In the same year, 1775, he was awarded a doctorate in music from St John’s College, Cambridge. He died in 1790 at 23 Rathbone Street in Bloomsbury following an operation to remove a stone in his bladder.

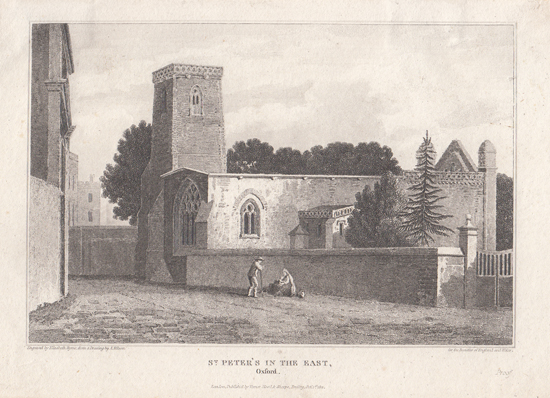

I am descended from Dr John Worgan’s youngest son, Joseph, who was born in 1768 shortly before his parents were divorced, and it has crossed my mind whether indeed John Worgan was his father. He must have been brought up by his two step-mothers until he was sent to school at Eton, from whence he attended Exeter College, Oxford, before taking holy orders as curate at Highworth in Wiltshire. In 1792 he married Jemima Hartland, whose father was a Lieutenant with the 41st Regiment of Foot (the Royal Invalids), serving as Town Adjutant in Berwick-upon-Tweed. You can read more about John Hartland HERE.

Joseph and Jemima stayed for six years in Highworth where three of their children were born, but then moved to Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds where Joseph was appointed Headmaster of the Free Grammar School there, a post he was to occupy for the next 25 years. Four more children were added to the family, among them my great-great-grandfather John Hartland Worgan. Joseph maintained his links with the church, becoming a curate in Chipping Campden and then in Pebworth, a village nearby, of which he would become vicar when he retired from the Grammar School in 1822. He died three years later.

The Rev. Worgan was a very heavy man and blessed with a hearty appetite. He was nicknamed “Bread-and-Butter Worgan” in consequence of his fondness for that form of food, and of an incident that is said to have occurred when he was on a visit to Old Comb Farmhouse. Present in the kitchen with the maidservant, who was cutting bread and butter for the tea he had been invited to partake of, he remarked to her: “Now, my wench! cut it thic’ o’ bread and thic’ o’ butter.

‘The History and Antiquities of Chipping Campden’ – by Percy C. Rushen (1911)

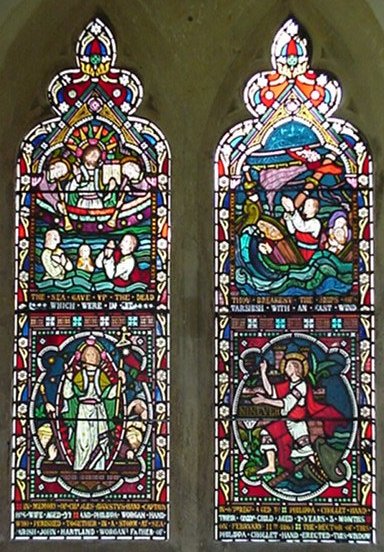

John Hartland Worgan, who was born in 1800, followed his father to Oxford and then into the church as curate at West Lavington in Wiltshire, where the vicar was William Mairis, the husband of his mother’s sister Anne, or Nancy. In 1835 he married Philippa Berney, a descendant of an old Norfolk family and distant cousin of a baronet. Their married life began in the little village of Catthorpe in Leicestershire where John had become curate and where all but one of their nine children – six girls and three boys – would be born. As the last girl, Frances Octavia, came into this world in 1848 John gave up the ‘cure of souls’ and the family lived in Cheltenham and Croydon over the next nine years, before returning to parish work at Willersey in Gloucestershire. It was while John and Philippa were there that their family began to disperse overseas. The first to go was the oldest, John, who joined the Indian Civil Service and eventually became a judge. Then in 1858 Philippa, the second daughter, married Charles Hand a captain in the army who had seen service in the Crimea. Tragedy was to befall them four years later when the ship they were on, taking them to Charles’s posting in Halifax, Nova Scotia, foundered in a storm in the Atlantic Ocean and they were drowned, together with Philippa, their two-year-old daughter, and the child’s nursemaid. Their tragedy is the subject of A Family Lost at Sea.

Prompted perhaps by John establishing himself in India, Philippa’s older sister Selina headed off there as well, marrying Anthony Falcon in Dinapore in 1863, only to die three years later leaving two small boys. Two years on from that my great-grandmother, Georgiana, also married in India. Her full name was Georgiana Harriett Charlotte Louisa – why so many when all her siblings had only two names? – and she married Robert Fuller Graham, then a tea planter in Darjeeling. More of them on the page about The Grahams. Georgiana’s younger sister, Constance, married Andrew Morris, the chief medical officer in Darjeeling, in 1878. That left two other children of John and Philippa: Philip embarked on a short naval career, training on HMS Britannia, a converted man-of-war, at Portland and seeing service around the world until he retired to Nova Scotia in 1871; and Frances, who remained in England, as youngest daughters often did. There had been another daughter, Mary Jemima, who died aged nine in 1851, and another son, Reginald Walter, who died aged only six weeks in 1848. Unlike his siblings he was born on the island of Jersey. Although both Georgiana and Constance returned to England in the mid-1870s, the latter only briefly as she and her family were to decamp to Tasmania, their parents will have seen little of most of their children.