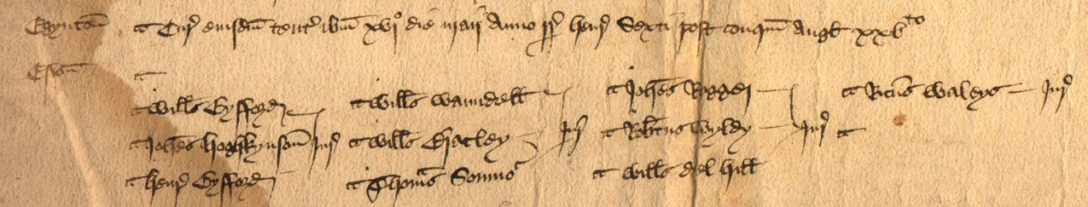

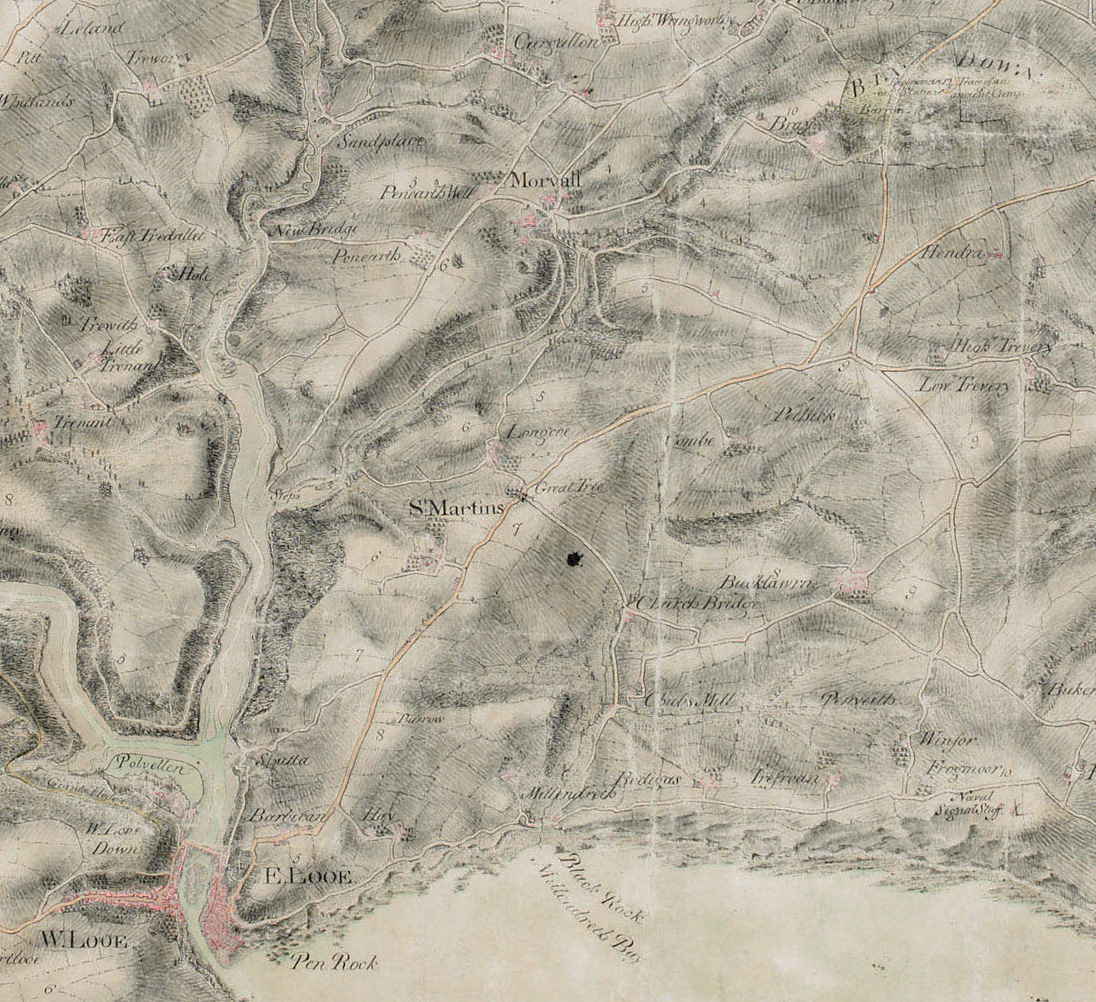

Charlotte Elizabeth was the youngest child of George Worgan and his wife Mary (née Lawry), and many of the writers who have documented the life of George Worgan have been unaware of Charlotte’s existence. George Boucher Worgan, to give him his full name, was the son of the celebrated Dr Worgan, organist and composer at the Vauxhall Gardens, and brother to Joseph my great3-grandfather. But although musical like his father and siblings, George chose a career as a surgeon in the Royal Navy, most particularly serving on HMS Sirius, the flagship of the First Fleet taking convicts to Australia in 1788. On retiring from the navy he had settled in Cornwall and taken up farming. He married in 1793 and he and his wife set up home in Morval, a parish north-east of Looe, where George leased two farms, Bray and Hendra. They raised a family of two girls and three boys, though at least one of the girls and one of the boys died in infancy.

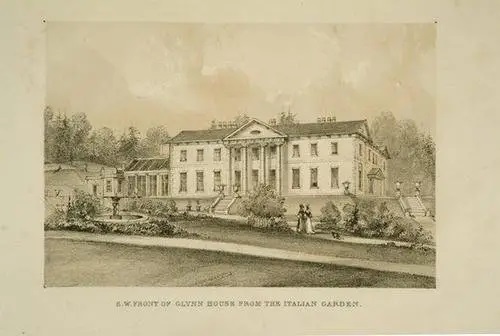

Ten years later, in 1804 the family moved to Cardinham, more than 15 miles away near Bodmin, to a farm George had rented attached to a large house called Glynn. It was there that their third daughter, Charlotte, was born two years later. She was probably named after her aunt, George’s sister, who was married to Sir Charles Parsons, the Master of the King’s Musick to George III. One of Charlotte’s brothers had been named John Parsons Worgan in his honour. The move to Glynn was not a success in financial terms. George failed to make the farm profitable and he vacated the lease after only two years.

Charlotte thus would have spent most of her childhood in Liskeard whence the family moved after George gave up farming and struggled to find useful employment. Eventually he took up teaching. In 1813 he was appointed headmaster of the new National School opened in the town. Charlotte would have been seven years old. Did she attend her father’s school? In Pigot’s Directory of Cornwall in 1830 the Worgans were living in West Street. We know nothing of Charlotte’s life until three years later when, at the age of about 27 she gave birth to a boy – Charles Parsons Worgan. The fact that he bore his mother’s surname indicates that she concealed his father’s identity. How his birth went down with the censorious social mores of the 1830s we do not know, but in the 1841 census Charlotte and Charles were living with Charlotte’s widowed mother at Wadeland House, Liskeard, which George Worgan had built in 1836, two years before he died. By then both of Charlotte’s brothers, George and John, had emigrated to Australia but of her older sister Mary nothing is known save that she was not mentioned in the will of their aunt Ann Lawry in 1845. She may not even have survived childhood.

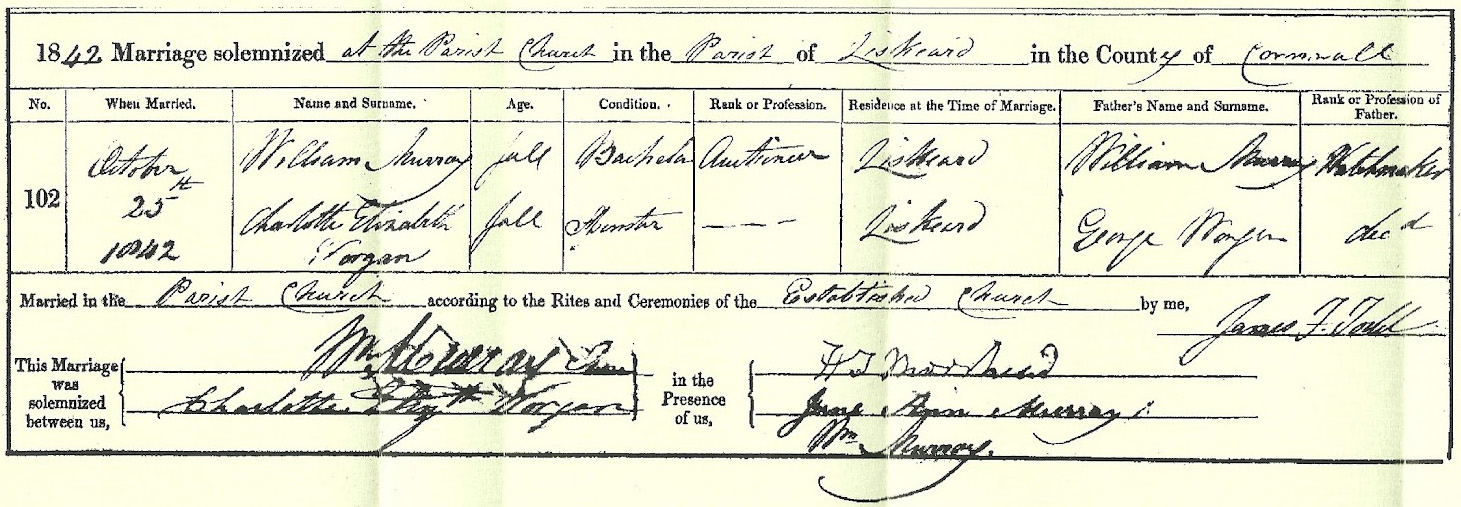

Having an illegitimate child, however, did not stand in the way of Charlotte getting married in 1842. Her husband was William Murray, a Liskeard auctioneer, and evidently William accepted Charles into his home. Ann Lawry had made Charlotte and her brothers the residuary legatees of her will, specifically leaving Charlotte’s portion “free from marital control, for her sole, separate and absolute use”. This may not have had anything to do with William and Charlotte’s relationship (they had only been married for three years), but is more likely to have been intended to give Charlotte some financial independence from the restrictions that married women had endured for centuries, that their husbands had sole control over their property. It was shortly after this time that campaigning began for the law to be changed, though it was not until 1870 that this came to pass. Ann Lawry also left £100 to Charlotte’s son Charles to inherit when he reached the age of 21.

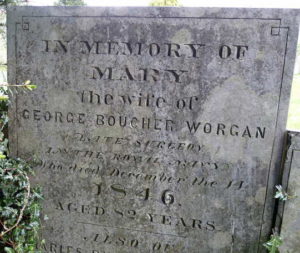

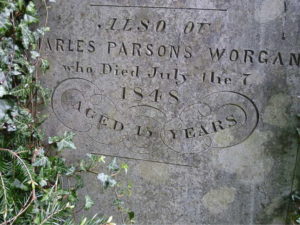

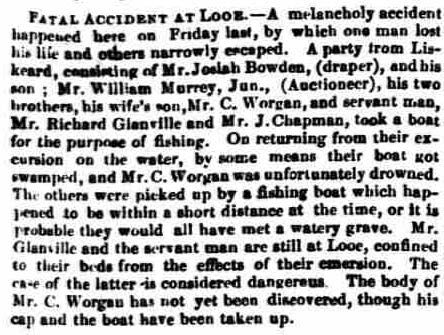

Charlotte’s mother Mary died in 1846, aged 82. Two years later tragedy struck when Charles was drowned during a fishing trip with his step-father off Looe. He was 15 years old. He was buried with his grandmother in St Martin’s churchyard in the town. One can never guess at how tragedy affects people but it may well be that Charles’s untimely death set in train the circumstances which contributed to the breakdown in Charlotte’s and William’s marriage.

In the 1851 census William and Charlotte are recorded as living in Castle Street, Liskeard, together with William’s young brother George and an elderly domestic servant. From their ages given then, Charlotte was eleven years older than William, and after nine years of marriage they were childless. Sometime during the next four years William Murray employed a young housekeeper by the name of Jane Whitford. In 1856 Jane gave birth to a son, Lewis William Murrayton Murray Whitford, and in the next four years two daughters, Edith Jane Whitford and Emma Mary Whitford. There seems little doubt that William Murray was the father. Was Charlotte understandably unwilling to engage in a ménage-a trois, or did William make it impossible for her to remain? Either way, Charlotte left the marital home, an action unthinkable for a wife over whom her husband had total financial control. But through the deliberate action of her aunt, Charlotte was not in such a position. In the 1861 census all three Whitford children had dropped their surname and become Murray although Jane was still described as housekeeper and unmarried.

In the same census Charlotte was recorded living, probably in one or two rooms, in a house in Compton Street in Plymouth occupied by eight other families. She was 55 and had no recorded occupation, although the money left to her by her aunt Ann would have given her some financial independence. Sometime after 1852 or 3 Charlotte had also benefited from a legacy of £100, plus a further £100 intended for her late son Charles, bequeathed to her by Ann Rowe, also of Liskeard, a neighbour of Ann Lawry. Miss Rowe’s connection with the Worgans is not known but Charlotte’s brothers were also beneficiaries.

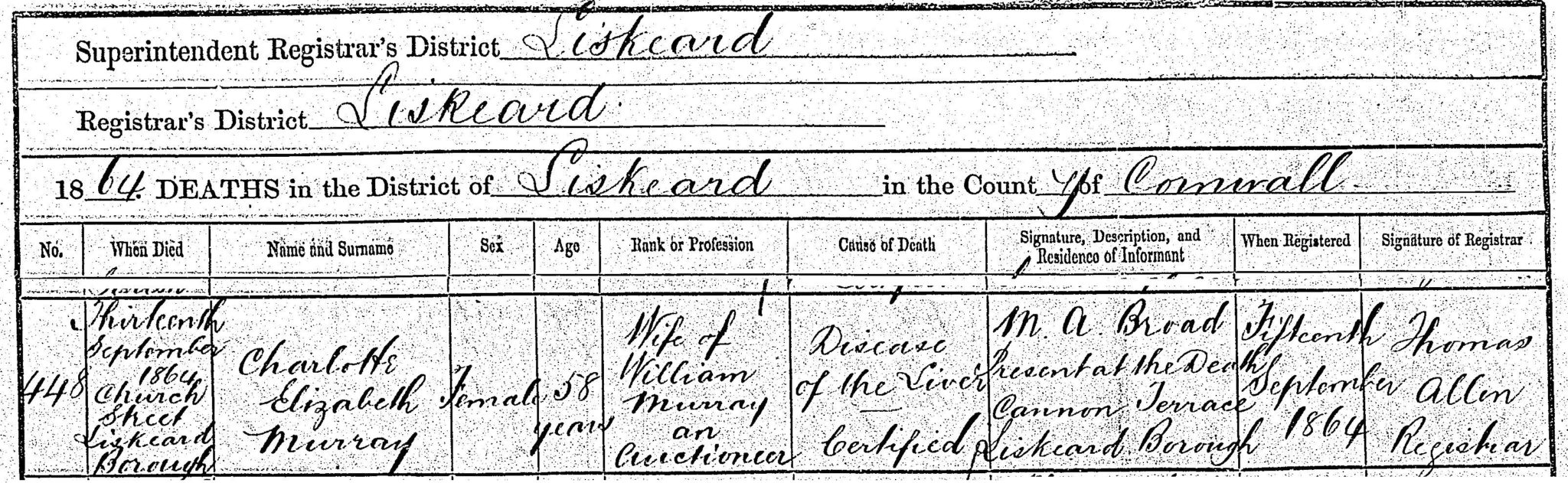

Although still resident in Plymouth Charlotte returned to Liskeard in 1864. She made her will nine days before she died, aged 58, on the 13th September at the home of Frances Tregellis in Church Street. The value of her estate was less than £450 (equivalent to about £47,000 today), from which she gave legacies to friends and, in particular, to the sons of Christopher Childs, her solicitor. She also left £20 to the Devon and Cornwall Blind Asylum which was on Coburg Street, Plymouth, close to her home in Compton Street.

Charlotte was evidently not reconciled with her husband, William Murray, who married Jane Whitford just over a month later. And was the cause of her death – disease of the liver – an indication that her life had spiralled downwards through an increasing dependence on ‘the demon drink’?