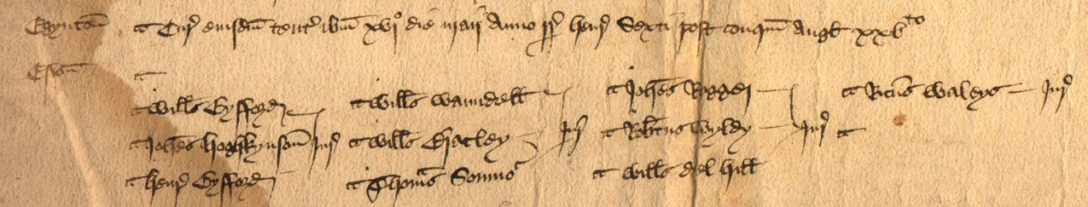

Family tradition had it that the Worgans were of Welsh descent but in 1679 it was from Newland in the Forest of Dean of Gloucestershire that John Worgan’s grandfather came to London to be apprenticed for seven years in the Pewterers’ Company. When he died in 1729 John was only five years old and the second youngest of the seven children of the second John Worgan, a surveyor, and his wife Mary, née Lambert. They were a musical family, with the eldest son, James, an accomplished organist and composer. He was to die, aged only 39, in April of 1753, and the next month his oldest sister, Mary, of whom we shall hear more later, was elected organist of the church of St Dunstan in the East in his place, the first woman to achieve such a position (although she resigned the next day to get married to Liell Gregg, a dealer in tea).

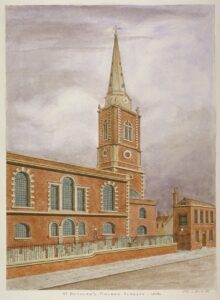

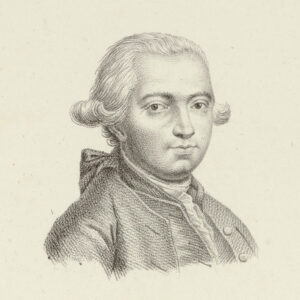

Five months later, on the 1st of September, John, her younger brother, married Sarah, the daughter of John Mackelcan, a sugar refiner. The wedding had taken place at the church of St Peter le Poer in Broad Street, close to where John’s widowed mother was living with his unmarried sister Ann. Sarah was five years John’s junior and had been a music pupil of James Worgan. John was 28 and described as of Clifford’s Inn in the court of Chancery. A legal career, however, was not his calling. In 1748 he had graduated in music from Cambridge and was already organist at two churches in the City of London – St Andrew Undershaft and St Botolph, Aldgate – as well as at the Vauxhall Gardens, the last two also in succession to his brother. John had also been a pupil of his brother before taking lessons with the composer Thomas Roseingrave, and the Italian virtuoso Francesco Geminiani. Through Roseingrave he became acquainted with the music of the Neapolitan maestro, Domenico Scarlatti, and John was later to obtain the rights to publish an edition of Scarlatti’s harpsichord music.

John and Sarah set up home at 7 Millman Street in Holborn, to the north of which fields stretched towards Hampstead. John’s responsibilities as organist at St Andrew Undershaft and, a short distance from there along Leadenhall Street, at St Botolph’s, would have meant his absence on Sundays for services. They were half an hour’s walk from Millman Street, but more than twice as far were the Vauxhall Gardens, via the newly-opened Westminster Bridge. He had been appointed as composer of songs and other music in addition to his job as organist the year he and Sarah were married. The Gardens were a fashionable and elegant venue and were open during the evenings from May to August, and John must have spent a considerable time there in the summer months. These responsibilities and the amount of time they took John away from home would be significant as time went on.

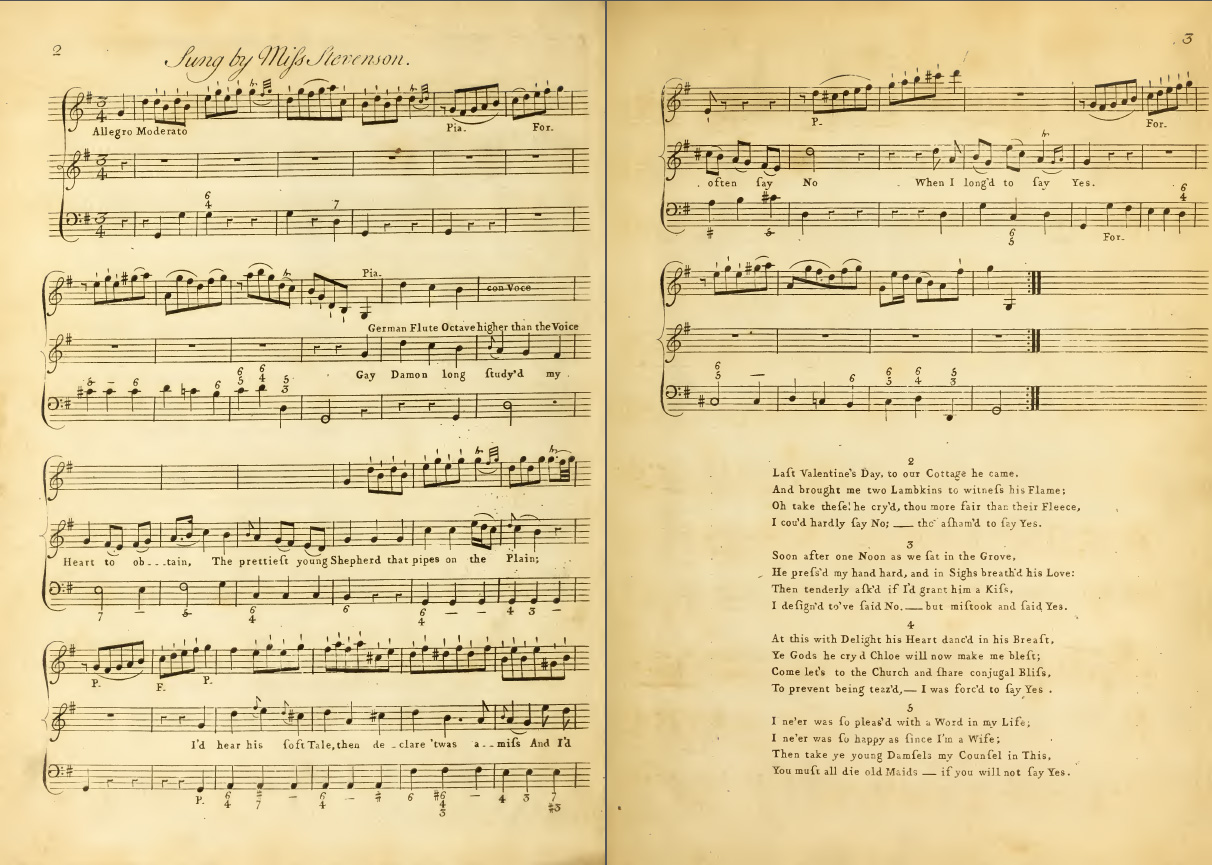

Within a month of their marriage Sarah was pregnant and that November she visited Bath, her arrival on the 3rd being noted in the local newspaper. John was not mentioned so perhaps he had stayed in London and she had been accompanied by her parents. Their first child, named after her mother, was born at the end of May 1754 and christened, as all her siblings would be, at St Andrew’s church on Holborn Hill. A year later a son, John, was born and three more sons, George, Anthony and Richard, during the following four years, their father supporting the growing family by playing the organ, teaching pupils and composing songs. Between 1754 and 1759 six collections of his songs for Vauxhall were printed for him by John Johnson, whose premises faced Bow Church in Cheapside.

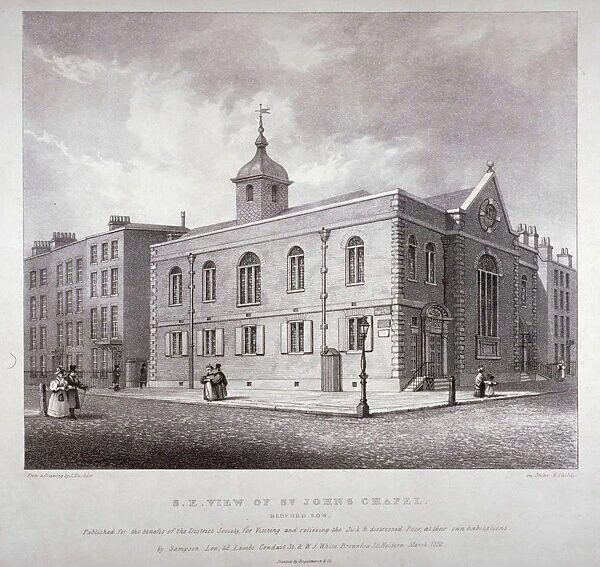

In June 1760 John was appointed organist at St John’s Chapel, a short distance along Millman Street, on the other side from where the Worgans lived. Already, he had begun to employ a deputy to play the organ for him when commitments to play at services in his three churches clashed. The first of the deputies we know of was John Langshaw. Born in Wigan in 1725, he had moved to London in 1754, where he became part of a circle of musicians, organists and inventors associated with the younger John Christopher Smith (1712-95), George Frideric Handel’s secretary and amanuensis. Smith had also been a pupil of Thomas Roseingrave and it may have been through Smith that Langshaw became acquainted with John Worgan. As well as playing the organ, Langshaw became involved in building chamber barrel organs which probably took up more of his time so that he ceased deputising, although he was to remain friends with John and Sarah Worgan. He was replaced as deputy that year by Robert Rowe.

Rowe had been born in about 1736 and had been apprenticed to Edward Rossiter of the Bakers’ Company for seven years from 1750. Whether he completed his apprenticeship is in some doubt. When, in May 1758, he married Elizabeth, the daughter of Joseph and Priscilla Vokins, at St Giles’ church, Cripplegate, he gave his occupation as ‘cabinet founder’, a maker of metal fittings for furniture. Had he gained his Freedom in the Bakers’ Company he would surely have given his occupation as ‘Citizen and Baker’. Over the next seven years he and Elizabeth were to have as many children. Evidently he also had learned to play the organ competently enough to be able to deputise for John Worgan. Anne Nichols, who was briefly employed as a domestic servant at Millman Street in about 1760, recalled Rowe being a frequent visitor both when John Worgan was at home but also, and in particular on Sundays when John was out, perhaps playing the organ at one or other of his city churches. In what was to become the pattern over the next few years, she related an occasion having come across Rowe in a compromising position with Sarah Worgan. Anne and the other servants suspected that they were having an ‘improper connection’.

The Vauxhall Gardens pleasure grounds lay on the south bank of the Thames, just to the north of Lambeth Palace, and John composed collections of songs for the resident singers to perform. Most were short and inconsequential, largely on romantic themes, but occasionally, when national events demanded, he composed patriotic songs. These too were popular; Thomas Arne, who wrote ‘Rule Britannia!’, was a contemporary of John Worgan and had previously been composer at Vauxhall. By 1761 John had published ten collections of songs, and the work to set them will have taken up much of his time when he was not playing the organ or teaching. Among his pupils at around this time was a young Irish singer, Robert Owenson, whose untrained voice had impressed Arne. John decided, that year, to relinquish his post as both organist and composer at the Gardens, and devote time to the composition of an oratorio to be entitled Hannah. At the beginning of September John and Sarah’s second daughter, Charlotte Sophia, was baptised at St Andrew’s church.

There appears to have been a fairly frequent turnaround of domestic staff at Millman Street. Anne Nichols had only stayed for a month in 1760. Katherine Bates was employed, she recalled somewhat uncertainly, in about 1762, staying for only five months, although six weeks after she quit she returned for a further four. During her time there she remembered that Robert Rowe frequently visited Sarah Worgan without John Worgan’s knowledge, deliberately choosing times when he was out in the city or at Vauxhall. She recounted an occasion when Rowe and Sarah were together, accompanied by Sarah’s three-year-old son, probably George or Anthony Worgan. Bates had heard the child cry and thought her mistress had called. She went to the door of the parlour but found it locked. Shortly, Sarah unlocked it and Bates noticed that Sarah’s and Rowe’s clothes were dishevelled and that they were both hot and discomposed. She took the child downstairs and asked him what Rowe had been doing to his mother and was told he had been kissing her and touching her neck. Later, Sarah and Rowe left for St John’s Chapel, Sarah telling Bates to tidy the parlour. On sweeping the carpet Bates found traces of semen.

As John had resigned his position at Vauxhall in 1761, Bates must have been at Millman Street a year earlier than she had thought. Anne Harcourt was more specific about when she had started work there, stating that it was in January 1762, quitting after nine months. However, she was to make no claims about any improper association between Rowe and her mistress.

Sarah fell pregnant again soon after Anne Harcourt had arrived, and in about September John and Sarah visited Bath. It was probably only a short stay for their fifth son James was to be born in November. They visited Bath again in June 1763, John visiting the Hot Wells at Bristol while they were there. Sarah was expecting her eighth child, who would be christened Mary, perhaps after John’s mother, in early January 1764. She would always be known to her family as Maria. Four months later, on the 3rd of April the first performance of John’s oratorio, Hannah, took place at the King’s Theatre in Haymarket, where many of Handel’s operas had also premiered more than 20 years earlier. The performance had been delayed by a few days owing to several of the singers being unavailable, and a second performance was cancelled. It was never performed again in John Worgan’s lifetime.

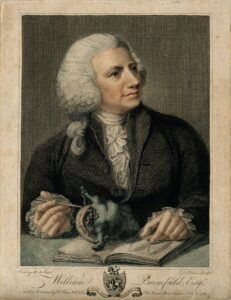

Around the end of July or the beginning of August John had cause to consult a surgeon, William Bromfield, about a discharge that was afflicting him and which he thought had the appearance of ‘clap’ but which he could not understand how he might have been infected with, having sexual relations only with his wife, whom, he told Bromfield, had been ill for some time. She had suffered a miscarriage and was suffering from ‘the whites’, a condition now known as leucorrhoea. William Bromfield was, in fact, a specialist in sexually transmitted diseases having, in 1747, founded the Lock Hospital in Pimlico Road for their treatment. Bromfield had met John some six years earlier when he was seeking a suitable venue for the performance of his oratorio. Bromfield diagnosed John’s infection as gonorrhoea, but acted with discretion by not disclosing to John his true condition. Some medicine was prescribed. A week or so later Sarah asked William Bromfield to visit her at Millman Street. Evidently John had told her about the condition he had sought treatment for and the diagnosis that Bromfield had given him. She thanked Bromfield for not disclosing the true nature of the illness to John for fear that he might reach the wrong conclusion about her. She claimed that she had been infected by a man who had scaled their garden wall and forced himself upon her. Again Bromfield acted with discretion and promised not to divulge to John what she said had happened, only doing so when John, four years later, had discovered his wife’s infidelity. Until then John remained in ignorance of Sarah’s infection. It had, however, been noticed by someone else. Martha Homer, who had worked as a servant at Millman Street in 1757, had continued to take in their washing. She had noticed staining on their linen that suggested to her that John had contracted clap. Significantly, perhaps, after having eight children in the previous ten years, Sarah would not become pregnant again until 1767.

The testimony of several witnesses to her infidelity with Robert Rowe belies Sarah Worgan’s explanation of how she was infected. From when Rowe had first been employed by John Worgan in 1760 he had been observed in compromising positions, or had been witnessed behaving in an over-familiar way with Sarah. Katherine Bates and Anne Nichols had been among those, although Anne Harcourt, who had been re-employed at Millman Street in 1764, had denied being aware of any impropriety. It seems that Robert Rowe had boasted to some of his friends that he had been having an affair with Sarah. Rowe had evidently ceased any trade he had carried on as a cabinet founder and had instead been employed as a clerk at a bank in Princes Street, Barbican. There he had befriended James de Hague, a fellow clerk, and had invited de Hague to join him and Sarah for a meal at the Worgan home. Rowe had claimed that he could invite anyone he chose to dine there. On that occasion Rowe had drunk to excess and had flirted with Sarah, taking liberties by kissing her and fondling her breasts. Sarah, de Hague was to report, had seemed offended, and he later remonstrated with Rowe about his behaviour. Another friend of Rowe’s, Charles Webb, from Cottenham in Cambridgeshire and, like de Hague, described as a gentleman, had also dined at Millman Street in John Worgan’s absence, and on two occasions had been witness to Rowe playing fast and loose with Sarah, she responding the first time with pretended coyness but the second time with evident anger and upset, to which Rowe had cried out, “Damn you, Madam, you know you are a whore,” and later telling Webb that he could do anything he liked with her. Webb came away with the impression that Sarah’s reaction in the first instance had betrayed the relationship between her and Rowe and that the second time she was annoyed that he had behaved as he had in front of a witness. Richard Synge, an upholder (dealer in second-hand clothes and furniture) of Whitecross Street, Cripplegate, was another friend of Rowe to whom he confided his affair with Sarah Worgan, telling him that the first time he had made love to Sarah he had declared that he was going to “cuckold the honestest man in the world”.

John was now working on a second oratorio, while continuing his teaching and his organ playing. In September 1765 he was invited to give a recital at the inauguration of a new organ at St Mary’s church, Rotherhithe. This was not the first time that John had performed such a function. A few months before he had married, he had been the first to play a new organ at the church in Enfield. He was much in demand to give recitals. At the beginning of 1766 John inaugurated the repaired organ at St Saviour’s church in Southwark, and later that year he was first to play the new organ at the Asylum chapel, presumably at the Bethlem Hospital at Moorfields.

John Langshaw, who had earlier deputised for John, had stayed in touch with the Worgans and had dined with them from time to time. He recalled an occasion in 1765 when he had supper with Sarah one Sunday when Robert Rowe was present, John Worgan not being at home. Langshaw remembered that it was in early November because a serious fire had occurred at Bishopsgate in the city, which had destroyed a great many houses. The thing that struck Langshaw was the free and familiar manner in which Sarah and Rowe spoke to each other, though he did not suspect them of anything untoward on that occasion. When Rowe left for the city to play the organ for John, Sarah showed Langshaw a note of hand for £60 (worth nearly £10,000 now) signed by Rowe which he had given her for sums of money she had lent him without her husband’s knowledge. She asked Langshaw how she might recover the money from Rowe without John finding out. Langshaw suggested handing it a third party who could sue Rowe for it; in that way it could not be traced to her.

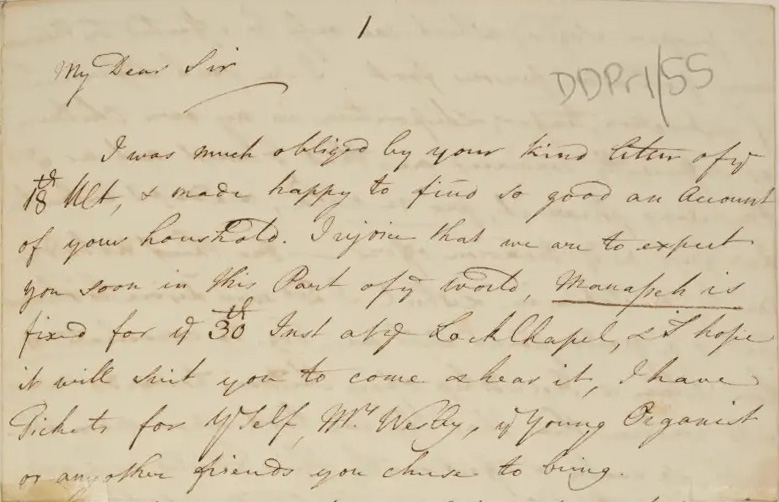

On 30th April 1766 John Worgan’s second oratorio, Manasseh, was given its premiere in the chapel of William Bromfield’s Lock Hospital. Martin Madan, the chaplain at the hospital and possibly the librettist for the oratorio, had written to the hymn writer, Charles Wesley, brother of the founder of Methodism, a fortnight before, telling him that he had saved tickets for Wesley, his wife and son and any friends he chose to bring. Wesley’s son, Charles was a pupil of Worgan and would play the organ at his master’s funeral.

My Dear Sir, I was much obliged by your kind letter of ye 18th Ult, & made happy to find so good an account of your household. I rejoice that we are to expect you soon in this Part of ye world, Manasseh is fixed for ye 30th Inst at ye Lock Chapel, & I hope it will suit you to come & hear it, I have Tickets for yrself Mrs Wesley, ye young Organist or any other friends you chuse to bring.

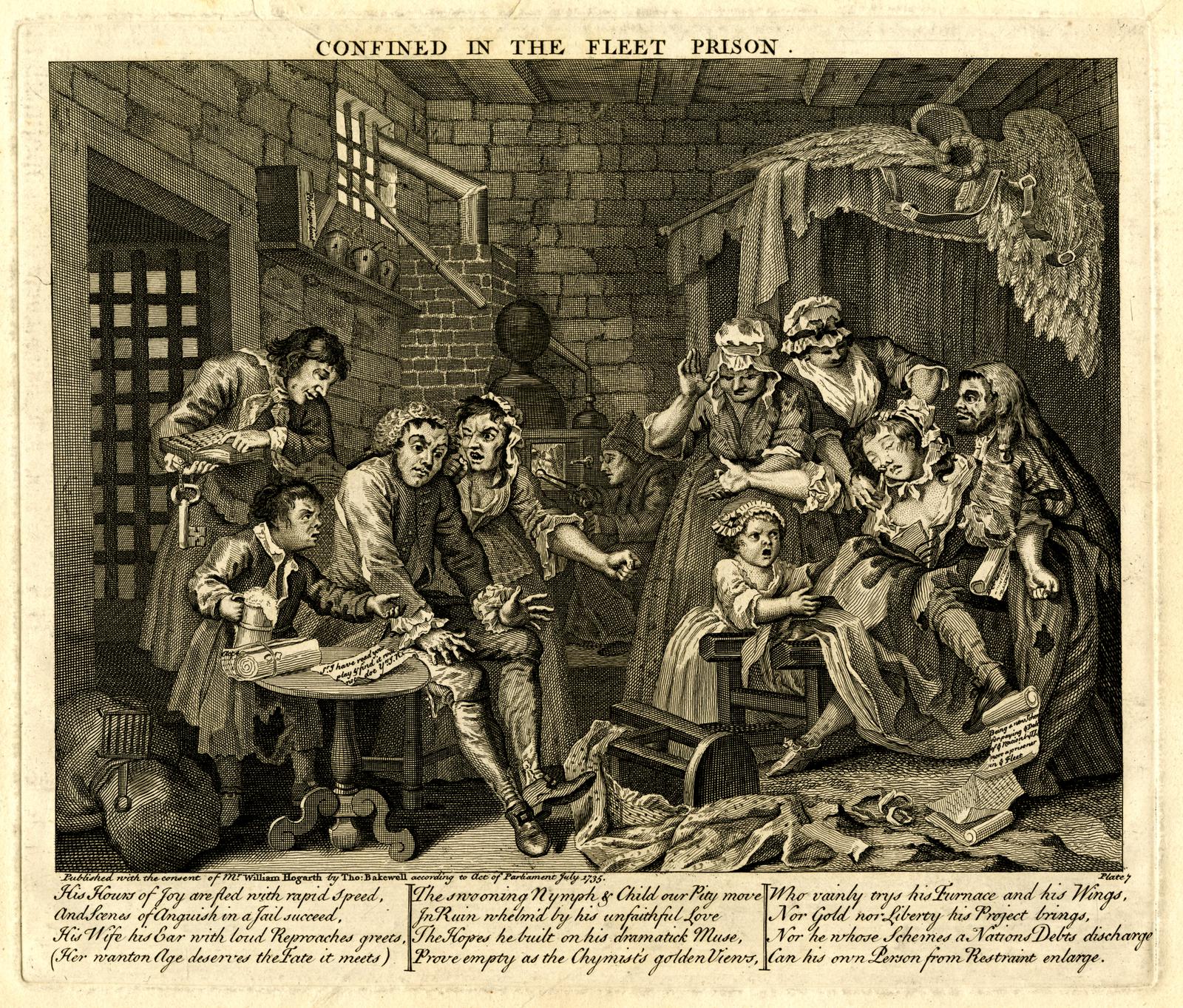

Sarah did as Langshaw suggested and gave the note to a Mr Batty, a butcher who had supplied meat to the Worgans. Rowe repaid him £25 of the £60 with the intention of repaying the remainder. However he failed to do so and in October 1766 Batty had Rowe arrested for debt and committed to the Fleet Prison.

All of this had been happening behind John’s back, although he must have become aware that Robert Rowe was no longer available to deputise for him, and perhaps also that he had been imprisoned in the Fleet for debt, although without knowing that Sarah had been involved. John continued to teach music, and in May 1767, Manasseh, was performed again at the Lock Hospital Chapel. A concerto by the popular Italian composer and violinist, Felice Giardini, was performed at the same event.

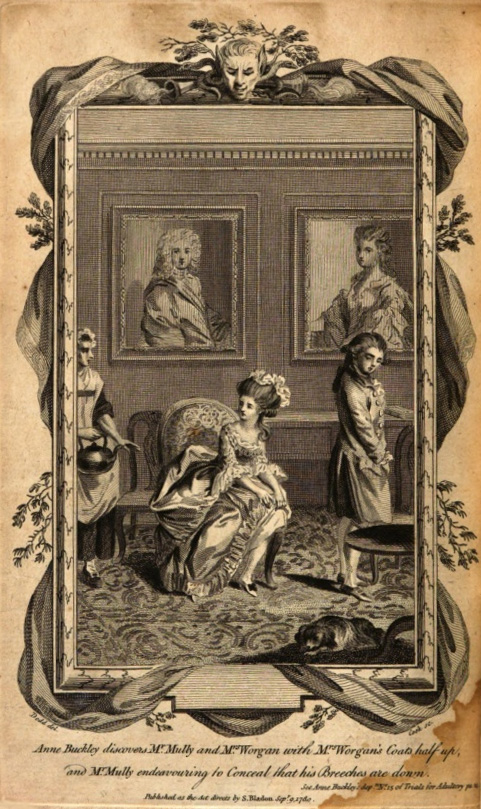

Two of John’s pupils at this time were John Mully and Arthur Kimpland. Ann Beckley, who had been employed as a domestic servant at Millman Street since the beginning of the year, related that on one occasion she had come upon Sarah and Mully in compromising circumstances, both with their clothes in disarray and hurriedly trying to compose themselves, and had concluded that they had been guilty of adultery. Sarah Worgan had accused Ann Beckley of drunkenness, that propensity being confirmed by Esther Harcourt who was employed in the house around the same time, and Sarah had threatened to dismiss Beckley. Harcourt recalled that Beckley had threatened to blacken her mistress’s name if Sarah did not give her a good reference. But it was not only Mully who had been carrying on with Sarah after Rowe had been committed to the Fleet. Another servant called Eleanor, who was Sarah’s nursery maid, had also caught her mistress “in a very indecent posture” with none other than John Langshaw. As will become apparent, this association with Sarah became public a year later, and it may be no coincidence that Langshaw and his family left London and went back to live in his native Wigan in 1770.

Another of John Worgan’s pupils was the daughter of Sarah Lalauze, whose husband Charles was the ballet master at the Covent Garden theatre. John had refused to take any money for her music lessons. Lalauze, as a consequence, became friendly with Sarah Worgan. On a visit to Millman Street in about July or August 1767 Sarah told Lalauze that, over a period of time, she had lent John’s pupil Arthur Kimpland £30 (about £4,500 in current money) plus interest at thirty percent, without her husband knowing, and that she had had to pawn a silver tea chest and other plate to recover the money, and that he must not find out.

Robert Rowe languished in the Fleet Prison for over a year, during the course of which he was visited by his wife Elizabeth, his mother-in-law Priscilla Vokins, John Langshaw, with whom he deputised for John Worgan, Charles Webb, and James Jones, whose wife, some ten or twelve years earlier, had been attended by Vokins in her capacity as a midwife. To each he admitted his affair with Sarah Worgan, claiming that she had seduced him and acknowledging the hurt he had caused to her family and to his wife, Elizabeth, who gave birth to their seventh child while he was imprisoned. He begged each of his friends to intercede on his behalf in persuading Sarah Worgan to pay to release him. He composed several letters to her, one of which has survived and reads as follows:

Mrs Worgan

Madm

Necessity or the Situation I am involved in through my misconduct chiefly owing to my so found attachment to your lustfull intreaties, calls now loudly upon me in this Dreadful place I am in to awaken your pretended Regard you always had for me –

Consider Madam the inconsolable distress the mortifying Circumstances that occasion’d it my innocent wife must now feel especially in her present situation –

Therefore I must in a very few words inform you what I declare would be to my friends themselves Excessive disagreeable that as there are people who are ready at the shortest notice to make Oath of our Wicked and Heinous connection* unless you do come to some settling of this debt you have levied against me to immediately get a Gentleman who will not leave me as you have done though in this Distress to wait on Mr Worgan and open the whole suffering that my poor wife in particular suffer and my self also I am &

Several of your letters

you know are in my possession

Wh we are determined to produce

*The Maid you turn’d away that I once kis’d in your presence because she look’d through the Key Hole as we was both upon the Carpet &c &c &c

James Jones called on Sarah and tried to persuade her to pay the debt to get Rowe out of the Fleet Prison but she did not and Rowe succumbed to the unhealthy conditions there and died on the 8th of November 1767. Sarah was already pregnant with her ninth child, my great3-grandfather Joseph, who was born in the following Spring.

Just after Christmas John Worgan fell seriously ill with a ‘pleuritic fever’. Often fatal in those days, this was probably what we now call pneumonia. John was only 43 but he had a large family to support and his condition was greeted with alarm to the extent that his widowed older sister Mary Gregg came up to London from her home at Betchworth in Surrey. She was accompanied by Prudence Jones, her companion, who stayed at Millman Street in the capacity of a nurse to John, while Mary, who had a house in London, visited daily. While Prudence was at the Worgans’ house she heard complaints by the two maids employed there, Elizabeth and Eleanor, that Sarah Worgan’s management of the house left much to be desired with bills unpaid and kept hidden from John to the extent that he risked being prosecuted. The maids accused Sarah of squandering money on other things despite John being generous in the housekeeping allowance he made her. The following day, when Mary Gregg visited, Prudence passed on the maids’ concerns, whereupon Mary interviewed them. They repeated what they had told Prudence and also told her about Sarah’s behaviour with John Langshaw and John Mully.

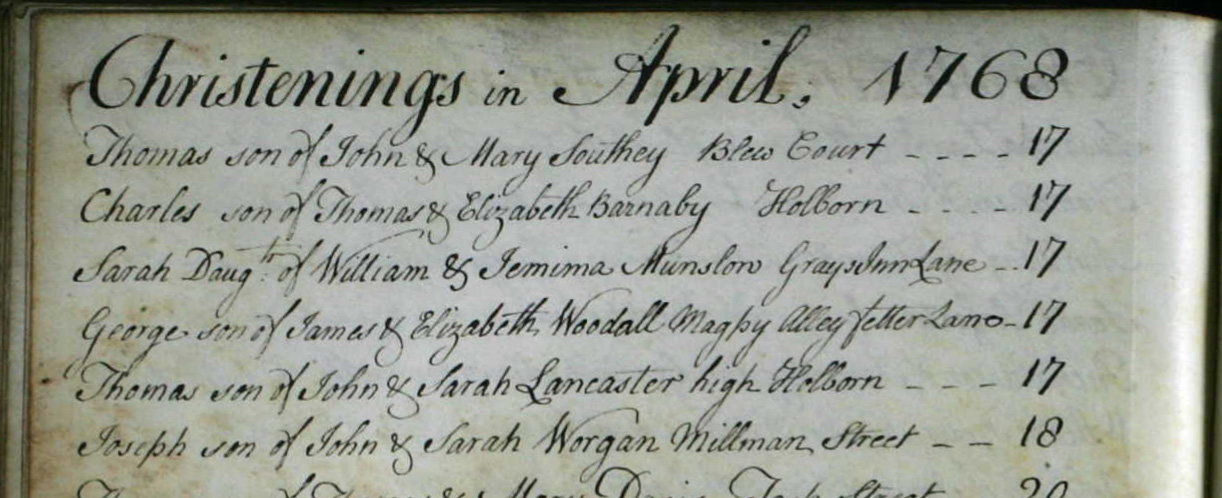

Clearly John Worgan was in no condition to be confronted with his wife’s misbehaviour, so Mary Gregg summoned Sarah’s younger brother Richard Mackelcan, a sugar refiner, to Millman Street and in his presence, confronted Sarah with what the maids had told her. Sarah admitted to an affair with Robert Rowe, by then, of course, dead, but denied what she had been accused of with Langshaw and Mully. To stave off the creditors Mary Gregg settled the outstanding bills and, with John showing signs of recovery, she went back to Betchworth for a few weeks, returning in February to acquaint him with what had transpired while he had been ill. At Mary’s house, where she had invited him to dine, John, who had had no inkling of his wife’s failings, initially refused to believe what his sister was telling him, believing that domestic servants were inclined to exaggerate, but Mary showed him the bills that had accumulated. A day later John declared that he would never sleep in the same bed with his wife again. What exactly happened next is not known. Sarah, by this time, was heavily pregnant so presumably they continued to reside in the same house until the baby was born, sometime in the next month or so. Did Sarah care for the infant Joseph Worgan or was he placed into the care of a wet nurse and a nurse maid, his mother being excluded from all contact with him and the rest of her children? Joseph, my great3-grandfather, was baptised at St Andrew’s Holborn on the 18th of April 1768.

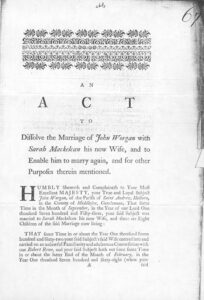

From then on, events moved quickly. On the 13th of June a divorce libel against Sarah was declared in the court of the Diocese of London. Hearings began on the 5th of July and continued until the 9th of November; no fewer than 22 witnesses were called by Mr Bishop, the court’s proctor, and notes written by Sarah and Rowe were exhibited (and retained) as evidence. The sentence of divorce was issued on the 6th of December. What resulted from this was a ‘separation from bed and board and mutual cohabitation’, removing John’s financial responsibility for Sarah but leaving several other matters undecided. The church ruling meant that neither John nor Sarah were allowed to marry again during each other’s lifetime. This in itself was a problem, for care of the children, particularly Joseph, needed addressing.

On the 26th of January 1769 John petitioned Parliament for leave to bring a Bill to dissolve his marriage and permit him to marry again. In his petition John stated that he had eight children then living. There is uncertainty as to which of his two oldest children, Sarah and John, had survived, no other record than that of their baptisms being known. They would have been 14 and 13 years old respectively. Of the others, five – George, 11, Anthony, 10, Richard, 9, Charlotte, 7, and James, 6 – were also of school age, Mary, or Maria, was only 4 and Joseph was still a baby. Following the sentence of divorce from the London consistory court Sarah ceased to live at Millman Street. Care of her children was probably taken out of her hands. The proceedings necessary in obtaining a divorce were expensive and most cases during this period involved wealthy aristocrats. Evidently John Worgan had the money to follow it through. Apart from being able to marry again and provide a step-mother for his children, he was also mindful of Sarah’s past behaviour and the risk that she might bear more children – spurious issue that could be imposed on him to succeed to his estate and fortune, as the petition to Parliament stated.

The First Reading in the House of Lords took place on the 15th of February and witnesses were called for the Second Reading on the 1st of March. Sarah Worgan was served with notice of the parliamentary proceedings. She was reported to be staying at a Mr Nicholson’s in Popes Head Alley, Cornhill. She told the parliamentary officer that ‘she had been used very ill’ but declined to say if she would attend. In the event, she was not represented when their lordships began to interview the witnesses, who were Catherine Bates, Ann Nicholls, William Bromfield, Mary Gregg and Elizabeth Rowe. After due consideration, the bill was passed by the Lords with an amendment and sent to the Commons on the 9th of March, who passed it with the amendment back to the Lords on the 22nd of March. On the next day the King, sitting in the Lords, gave his assent.

As part of the amendment to the Act of Parliament, reference was made to a deed drawn up on the 21st of March 1769 between John Worgan, Sarah Mackelcan (formerly Worgan), Edward Rowe Mores of Leyton in Essex, Esquire (Sarah’s mother’s nephew), and James Oram Clarkson of Castle Court, Lawrence Lane, London, Gent. (son of John Worgan’s sister Hannah), for the maintenance and support of Sarah after the passing of the Act. It would be very interesting to discover the contents of this deed, suggesting, as it appears to do, that John Worgan had not cast Sarah out of his life without anything to her name, perhaps in consideration of the fact that she was his children’s mother.

So who was the instigator of this affair? Robert Rowe maintained to all of those who visited him in the Fleet Prison that Sarah had seduced him, although he clearly had entered wholeheartedly into the affair and had been emboldened to the extent that he had bragged about it to his friends. But Sarah seems far from blameless if the reports by her servants were to be believed. For, after Rowe had been committed to the Fleet Prison, she had carried on with John Langshaw and John Mully.

Nine months later, John Worgan married Eleanor Baston at St Andrew’s, Holborn.